Reading Under and Around the Lines and Lemmas

Manuscript Ottoman Qur'āns and the Nature of Early Modern Textuality

I’d like to take a slightly different tack in this essay than usual, taking you through a series of points in a small corpus of manuscripts—mostly in Ottoman Turkish and Arabic but also one in Persian—which may not seem immediately related but which I hope ultimately carry through to some, dare I say, profound insights into the nature of textuality in early modern cultures. My order of approach here will reflect the original order of discovery from a recent session of the Ottoman Turkish manuscript reading group I am facilitating this summer, as we worked through a Qur’ān tefsīr—commentary, though the suitability of that translation is questionable in this context—following leads as we went. As such my thoughts here are by no means mine alone (not that one’s intellectual work is ever sui generis, no matter how exceptional or brilliant) but reflect our group process of reading and interpreting and puzzling out the paleography, layout, meaning, and correspondences. I should note that Ottoman Turkish, especially older texts from the initial centuries of the language’s development, tend to be challenging for everyone, native modern Turkish speakers as well as those like myself who learned the language via Persian and Arabic (and whose modern Turkish is woefully inadequate). Orthography never really fully stabilized, and as we will see in older texts especially it was especially erratic!

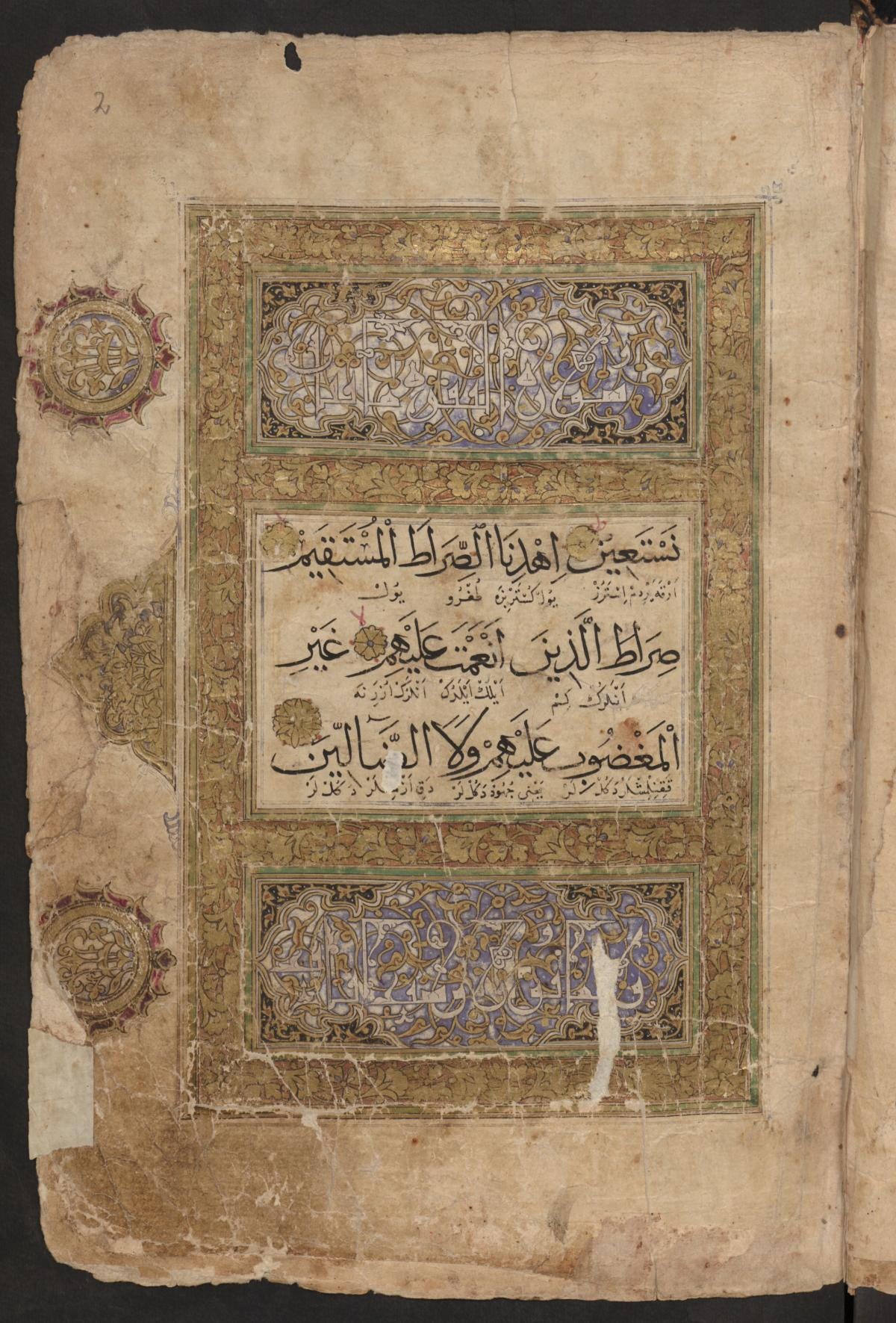

i. title page traces

Our main manuscript for this session was Tefsīr-i Qūrd Efendī, SbzB Hs. or. 1066, a 16th or 17th century commentary—well, really more of a translation with sporadic commentary passages—about whose author I could not tell you anything more, with no personal information to speak of contained within the text itself. In fact the only indication of an author’s name at all comes from the above very worn by time and use “title page,” an appellation that does not feel quite apt really. At the top of the above selection the title can be made out, half of “Efendī” missing. But most of this page is taken up by other things: below the title is evidence of a pen trial or calligraphy practice, while below that is the notice of the death of someone named Mollā Ḥasan in the year 1039, that is, 1629. The numbers and words on the left hand side of the page, which, along with the death date notice, occupy the original paper, the page having been repaired at some point in the manuscript’s life.

This sort of thing are common in manuscripts: paper was much scarcer in the early modern Ottoman world than in our time of mass material affluence, and the front and back pages of many manuscripts gradually accumulated texts, doodles, calculations, and other inked ephemera, often added by someone simply in need of some paper upon which to write or draw or reckon (family Bibles in Latin script contexts are very similar in this regard). Sometimes the person in question left his name and perhaps a date, especially in the case of ownership and reading notices, but most other scribbles and doodles are undated and totally anonymous. As such they have a certain pathos, quite possibly the only remaining tangible traces of entire human lives from the past, lives that however briefly intersected with these pages which have survived the exigencies of history and now appear on our computer screens.

ii. rendering the Qur’ān in Ottoman Turkish

As I’ve discussed in these pages before, it really is the case that in premodern Islam (and almost overwhelmingly in modern Islam as well) the perceived intrinsic connection between the Arabic of the Qur'ān and its status as divine speech was believed to be and was treated as inviolable. Hence the preferred format for translation, whether in Ottoman Turkish or in other languages, was either interlinear or, as in this example, a lemma by lemma approach, the translation hewing close to the original Arabic both visually and semantically. This contrasts with translation of ḥadīth, authoritative but much less fixed texts, which are usually translated in single blocks, not lemma by lemma or through interlinear. In the example page below (which has at its header the indication of ownership by someone along its chain of custody; not the repair that was done to the paper) you can locate the Qur’ān lemmas thanks to the overlining:

Translation of the Qur’ān was not rare: the semantic meaning of the text mattered alongside its other understood uses and powers, and from a relatively early date the Qur’ān was being translated and interpreted using Persian. As Ottoman Turkish emerged as a medium of communication it is hardly surprising that it too would become a language of Qur’ān translation and interpretation, given that effective knowledge of Arabic would have been quite limited in Anatolia and the Balkans. Arabic was taught, to be sure, but particularly in the late medieval into earliest early modernity Persian was the dominant second language for learned Ottomans, and of course the majority of the population would not have known either tongue. As such translations of the Qur’ān could have served both literate people and non-literate audiences; we can easily imagine mosque preachers making use of texts like our tefsīr in explaining the Qur’ān to their congregations.

One of the incredible boons of the digital age when doing this kind of reading is the easy—perhaps too easy, but that’s another discussion!—availability of multiple exemplars of a text, and the relative ease with which we can peruse two or three such texts side-by-side. As such after a little while working through this text, which on the whole is not especially challenging linguistically (plus in cases of unclear meaning we can work backwards from the Arabic text), we decided to look at another Ottoman translation of the Qur’ān, pulling up an interlinear version from 1478, more or less at random. Here is the opening page:

While mostly a “literal” translation, at times it undertakes subtle but very much overt interpretative interventions: for instance, in the final lemma of the Fātiha, where our tefsīr has a basically literally rendering of the Arabic, the Qur’ān interlinear expands by translating the phrases “not those with whom you are displeased” and “nor those who are misguided” into Turkish, but adding to the literal translation “meaning: not the Jews,” and “not the Christians.” Of course there is no indication in the text itself as to which groups, if any, are intended; our translator no doubt had access to a tafsīr or some other written or oral text which made this interpretive move, and decided to incorporate it into his translation.

While the two translations tend to coincide on their word choices, they are not identical, and sometimes make quite different choices. For instance, the tefsīr translates (or doesn’t, rather) “Allāh” simply as “Allāh,” while the interlinear translates both “Allāh” and “Rabb” as “Teŋri/Tañrı,” the more natively Turkish option. I don’t think we should or could read much into this sort of choice: it is not uncommon to see Ottoman authors vary between the two possibilities, though generally speaking the more likely a text was geared towards a purely vernacular-speaking context the more likely the Turkish rendering of “God” is to appear.

Something else that will be immediately evident to anyone who can read Arabic script in both our tefsīr and the interlinear Qur’ān is the fact that their consonantal skeletons are all fully vocalized, for both the Arabic—not a surprise there—and for the Ottoman Turkish. The purpose of vocalizing the Turkish does not seem to primarily be a matter of comprehension, since in most cases the meaning and pronunciation of the words would be clear to even a marginally literate person. Rather, vocalization seems to have functioned as a marker of the text’s sacred or canonical status, a practice that is visible in contemporary Arabic texts as well, and one that carried over into the age of print. While the majority of Ottoman publishers’ printed output was done with metal type, lithography (which is essentially mass-produced manuscript production) was used for certain texts, primarily canonical devotional ones like the Dalā’il al-khayrāt or the Muḥammadiye. And while the vocalization is usually correct, we have encountered instances in which it appears as if the scribe simply added fatḥahs to every consonant whether or not it was correct! In this instance the visual aspect of the text outweighed the aural and the semantic.

iii. interpretative forays

As it turned out, what was advertised as a tefsīr, that is, a commentary, was really more a translation. However, at certain points the author does include snippets of commentary, pulled from somewhere in the tafsīr tradition. For instance, our author decided to devote some space for more expansive commentary in relation to the opening words of Surat al-Baqarah, or, rather, the opening letters: ālif, lām, mīm, written connected together though they form no (known!) lexical unit per se. Much ink has been spilled as to the meaning of these and other mysterious such letters, the ḥurūf muqaṭṭaʿāt. In our tefsīr the author provides two possibilities: first, according to the famous ḥadīth transmitter Ibn ‘Abbās, the letters mean “I am God, I know (Anā Allāh aʿlam),” given first in Arabic and then rendered in Turkish as “I, I am the God (here Tanñrı) who is the knower of the unseen.” However, unnamed “others” say that “the alif is Allāh, the lām is Jibra’īl, and the mīm is Muḥammad.” The reader can choose which interpretation to go with. By contrast, the interlinear only gives the Ibn ‘Abbās option without further comment.

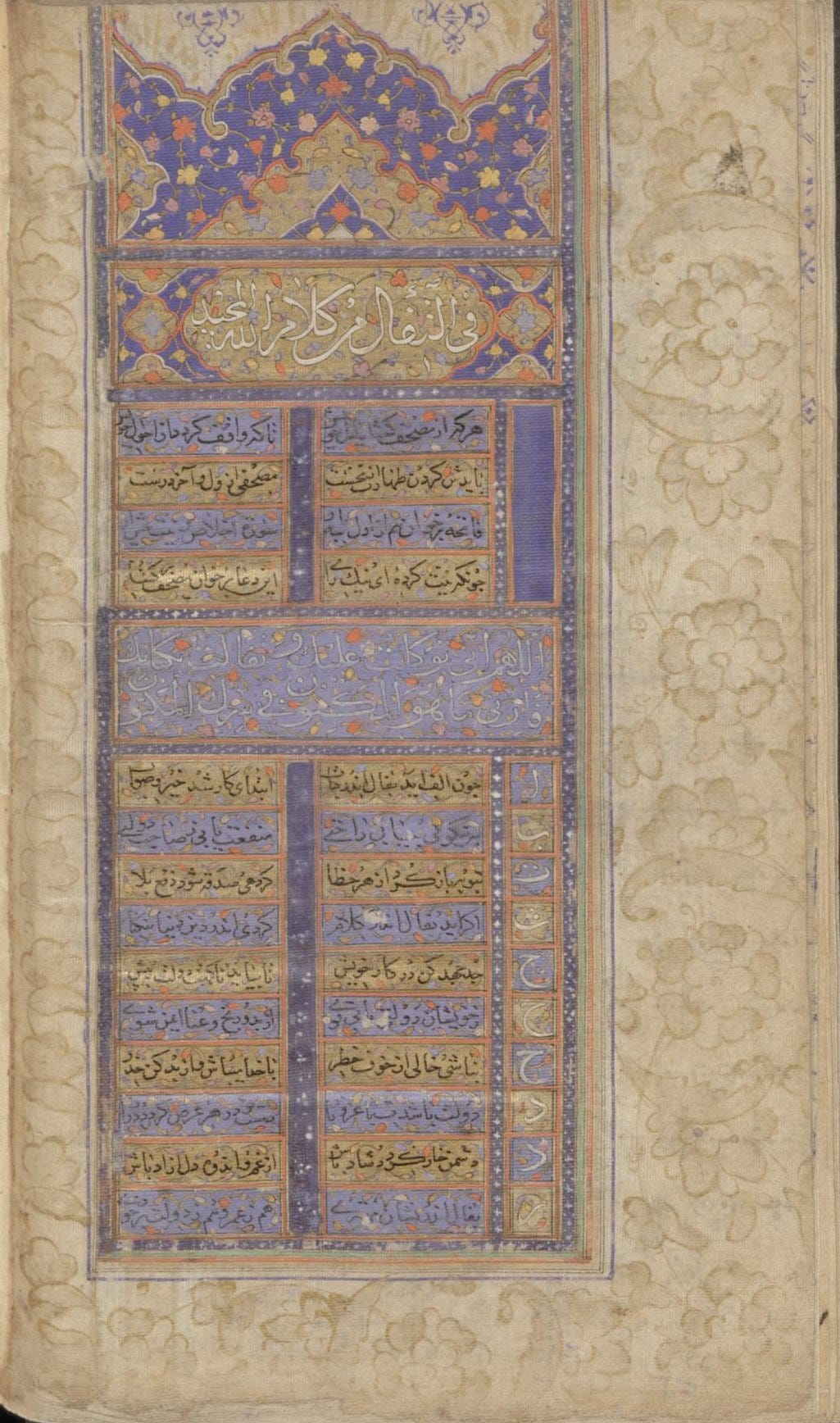

iv. fāl

After examining the above interlinear Ottoman Qur’ān’s first pages and comparing them to the tefsīr’s, we decided to have a look at its colophon, in this case not especially revelatory beyond giving the date of completion and the location, Edirne. What was more striking to us, however, was the little text included right after the single-line colophon: the first line reads fāl-i Qur’ān, while similar texts are sometimes titled Fāl-nāmah, among other things. Fāl is a term that means “divination,” and in the case of fāl-i Qur’ān, “divination by the Qur’ān,” sometimes translated as “bibliomancy.” The idea here is relatively simple: the one seeking insight randomly selects a page and a letter within a codex of the Qur’ān, the fāl-nāmah then providing an explanation for what each letter means. For instance, as the Persian version below has it (my translation attempting to match the rhyme), “When within this Book it is upon alif that you alight / then the beginning of [your] work will be good and right.” As might be imagined, the prognostications are fairly general, potentially applicable to anyone’s situation.

While there have been Christian instances of a similar practice, sometimes referred to as sortes biblicae, they have been rather more marginal and consistently frowned upon in theological pronouncements. In the Islamic case, a convergence of different theological currents has served to make this sort of practice rather more respectable in the eyes of the ‘ulāmā’, though as with all these semi-magical practices and arts things can go both ways. Sometimes divination methods, the writing of talismans, and so forth are perfectly acceptable, sometimes not so much; the reasons for often quite different evaluations are complex and beyond our scope here. The theological rationale is rooted in the nature of the Qur’ān in virtually all iterations of Islamic theology as being the literal locution of God expressed in the literal letters of the text, which, when combined with belief in the overwhelming nature of God’s willed direction of the cosmos makes prognostication by “random” landing on letters a not unreasonable conclusion.

For whatever reasons, fāl-i Qur’ān texts in Persian, Ottoman Turkish, and Arabic seem to have become more common in early modernity, though that could well be an example of survival bias, I’m not a hundred percent sure. In some cases, though hardly all, they are prefaced with the name of some sanctified authority figure, implicitly or explicitly rooting the veracity of the fāl pronouncements in that sacred figure’s knowledge (Imām Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq is a frequent choice, given his well established connection among both Sunni and Shi’i Muslims as a possessor of esoteric knowledge). They are often found at the end of a Qur’ān codex, especially in the Safavid context, but they also exist as discrete texts on their own and as additions to other compilations and texts.

v. conclusions

What else can we learn from this bevy of discoveries? A great deal, I would suggest, about how early modern Ottoman readers and users (for the two are not necessarily the same thing!) of the Qur’ān understood their sacred text and the nature of texts, of letters, of books, more generally. I say early modern Ottoman, but as we saw with the fāl-nāmah, most of what can be revealed with these specifically Ottoman examples would apply to other medieval and early modern Islamicate contexts to varying degrees.

Two things are simultaneously true about the textual ethos operative about and constituting these Qur’āns and their surrounding structures: one, the semantic content of the Qur’ān, its meaning and meanings, mattered. While, unlike in Christianity, stand-alone translations of the Qur’ān were, and are, virtually non-existent in an Islamic context, the sacrality of the text being inexorably linked to the Arabicness of the text, this did not preclude interpretation in other languages, de facto translation, so long as it was visually tethered to the Arabic. Readers and listeners of the Qur’ān whose command of Arabic was poor or non-existent still wanted to know what it meant and to be able to interpret it, a task that had long been valorized under the rubric of tafsīr and which was extended more or less readily into other languages.

Yet at the same time, as the constant visual and spatial proximity of the Arabic text of the Qur’ān would indicate, and as the logic governing the fāl texts even more strongly suggests, semantic content, the translatable meaning of the text, was only part of the story, only part of the experience. The materiality of the Qur’ān—including, I think, in the case of the tefsīr in which the Qur’ān was embedded in a non-Arabic text—functioned as a sort of holy site, one within which inscribing the name of a friend or neighbor who had recently died made sense, for instance. The letters themselves possessed a potency that was not determined by their semantic function, but which could be abstracted out via bibliomancy. Their very appearance—vocalized to indicate sacredness and canonical status—had a power and charge, including for those who were completely illiterate.

Finally, I want to note that all of the above came out of our group reading and discussion of these texts, reincorporating quite old manuscripts into a similar aural, group culture for which they were first made and out of which they emerged. I did some follow-up research afterwards, precipitated by the things we came across and discussed, but would not have done any of it without that first round of interaction with other people. Our interaction was mediated by the internet—we meet via Zoom, and use a combination of online platforms for sharing work, ideas, and manuscript files and images—though mediation of manuscript texts over distance is not new. Indeed translations are examples par excellence of the movement and transformation of texts through time and space, a movement that continues in our own world with a different suite of tools, geopolitical realities, and all the rest, but with many of the same fundamental structures still present, including awe for the text itself in its materiality and beauty.

♥️