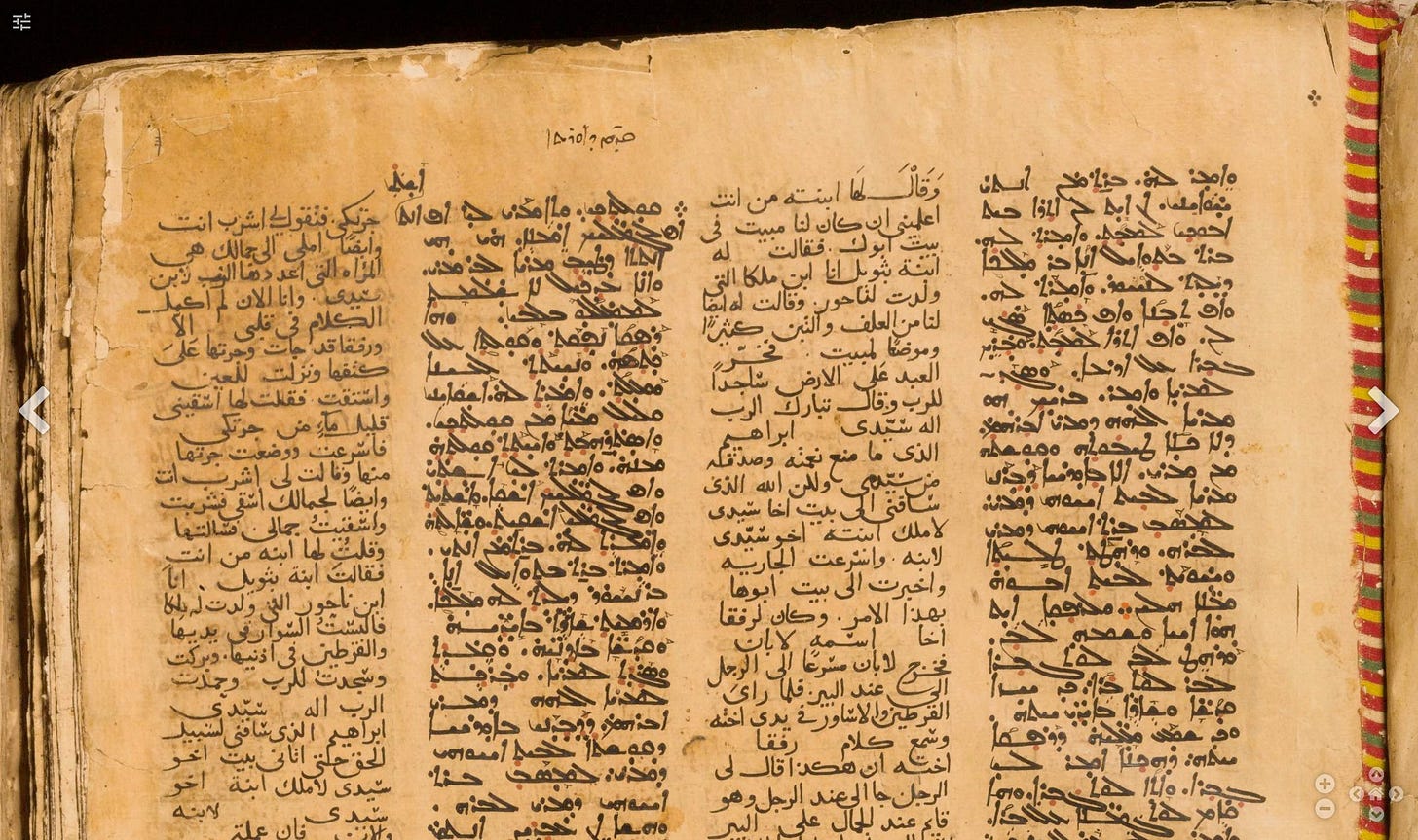

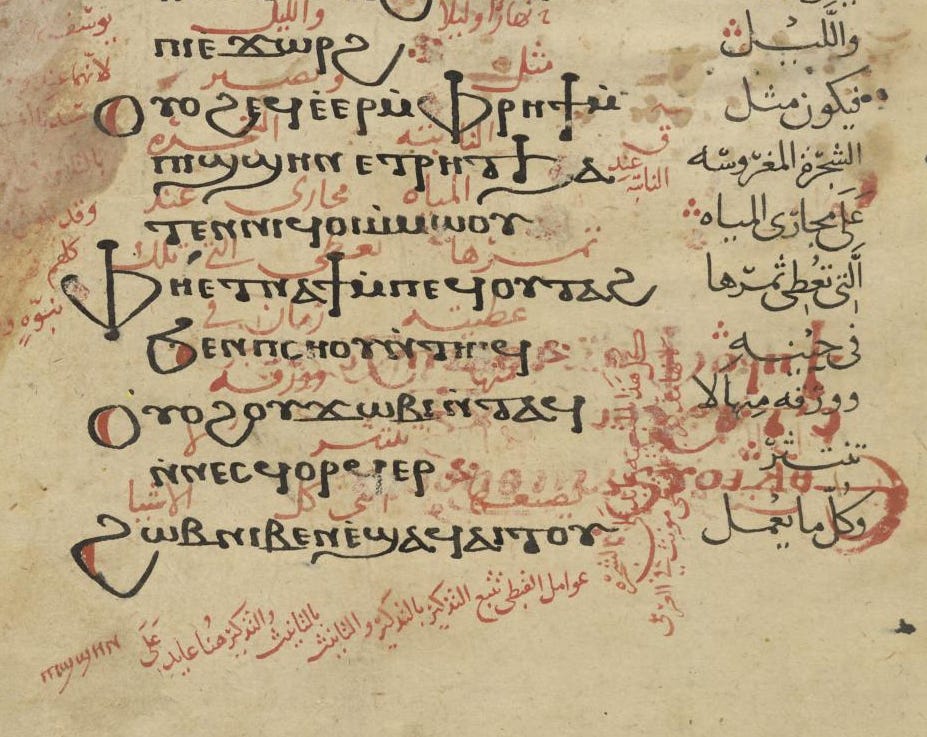

Something I’ve long noticed about Islamicate manuscripts cultures—understood in the broadest sense, including Syriac, Armenian, and other non-Muslim traditions, some of which have extensively incorporated Arabic script, others of which have not—is that there is a marked confessional divide in the arrangement of text, specifically whether a manuscript incorporates ‘true’ columns or not. For two salient examples look at the above: the first image is of an anonymous commentary on the Qur’an copied in the 15th or 16th century, with the main text in Persian, the larger script the Arabic of the Qur’an, with slightly slanting interlinear translation below each word. Below it is a selection from a translation of and commentary on the Book of Genesis into Syriac and Arabic, the two languages in parallel columns, the Arabic commentary in a single column above and below the translations. When columns appear in Islamic texts, they are rarely true columns but are meant to be read straight across, as in this random Persian example pulled from a manuscript with which I was working this morning:

By contrast, Syriac Christians sometimes made use of true columns even when writing only in Arabic, as in this 18th or 19th century example, in which each column is read from top to bottom and then over to the next column:

I am not an expert on Syriac mansucript culture or its late antique cousins, but my sense is that the use of true columns emerged early and in dialogue with other linguistic traditions. Armenian manuscripts follow similar conventions, either due to a shared milieu of emergence or in imitation of Syriac manuscript culture.

What is interesting to me is the fact that, so far as I can tell, once Arabic began to be written on parchment (and eventually on paper) no one divided texts into parallel columns. Every early Qur’an of which I am aware is single column, regardless of the page format. And once “translations” (the term is not really quite apt, at least for the medieval and early modern period) of the Qur’an began to appear, they did so not in the form of parallel columns in Arabic and in the language of translation (bi- and tri-lingual non-Qur’anic texts in multiple true columns do show up later in the manuscript tradition, but they are something of a novelty, usually a display of an author’s skill in multiple languages as much as anything else). Rather, Muslim scribes used interlinear methods to translate the text into other languages: this could entail lemma by lemma translations, with the words often at a slant (see below for another example, this one in Ottoman Turkish), or it could be in the form of a more continuous line subordinated to the main text, as in the second example below.

While as mentioned before there are exceptions of multilingual texts with parallel columns, interlinear or alternating line texts in two or more languages would remain the rule in Islamic manuscript culture, as can be seen in this eighteenth (probably, might be nineteenth) century instance of a Persian text (with abundant Arabic included within it) along with an alternating Hindī translation in red ink:

What explains this curious divergence in manuscript cultural styles? It is clearly not a case of the affordances of the respective scripts: Arabic can be written in multiple columns, and indeed during the early modern period manuscripts were often written with multiple nesting layers of text, sometimes with a core central one and flanking marginal texts but sometimes with a non-hierarchical swirl or mixture of discrete texts arrayed across the page.

My suggestion—and this might well be wrong!—is that the key lies in translation, specifically translation of Scripture, and the underlying theological visions that developed in Christianity and in Islam (reinforced over time by the shape and appearance that manuscript texts took, no doubt). To over-simplify somewhat, Christianity in the late antique period (if to a somewhat diminishing, for a while, extent later) took a fairly open stance on translation, treating Latin, Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, and so forth translations of the original Greek (which included the translation of the Hebrew Old Testament into Greek) as basically equivalent to the orginal. Indeed there are often suggestions that multiple translations could, as it were, expand the ambit of Scripture’s meaning and reach. In short, translation, manscript variability, and so forth did not create a great deal of anxiety among late antique and early medieval Christians. Scripture was inspired, to be sure, but it was not regarded as uncreated or even invariable. The situation was quite complex on the ground, and most Christian thinkers insofar as they engaged with such questions felt relatively at ease with variance and variability, including across translational lines. As such there was less felt need I think to subordinate a translation (or, in the case of Syriac version of the Bible translated into Arabic, a translation of a translation!) to the “original” text.

Now, while it is certainly true that the doctrine of the uncreated Qur’an developed over time, the seeds thereof are pretty clearly present from the beginning, and were reflected I think in the form that early Qur’anic manuscripts took. And certainly the emergent doctrine of the uncreated Qur’an shaped the Qur’an’s manuscript tradition, into which early medieval scribes would add interlinear “translations,” an intervention which was itself debated as to its propriety. For the uncreated quality of the Qur’an lay quite literally in its original wording, its “Arabicness” an essential quality, not a more or less incidental or at least contingent one as was often the case in late antique Christian understandings. Any translation or interpretation therefore into another language needed to be visually subordinate to the text of the Qur’an—hence the use of interlinear, often in a different script and smaller size, often at a slant from the horizontal main text itself. Parallel columns simply would not, could not, indicate the proper relationship, suggesting as they did an equivalency of value and meaning.

There are no doubt other factors that help to explain this peculiar marker of confessional identity. For one thing, as the medieval period progressed, most Christian communities saw a decrease in the use of their “original” languages, Coptic, Syriac, and others slowly becoming more and more liturgical and learned languages, and then only liturgical, as their antiquity and association with the first period of the faith tended to sediment them into semi-sacred status. As such Christian communities tended to need multi-lingual texts more often I suspect than their Muslim neighbors. And to be sure Christians adapted similar strategies to Muslim scribal cultures (which after all were not sealed off from one another but on many fronts interpenentrated); the following instance of a Coptic main text with both an Arabic lemma by lemma interlinear and a parallel column of continuous translation is a good example of such dynamics:

There are lots of questions which remain in my mind: for one, is my explanation above at all correct or satisfactory? I’m not entirely convinced it is, though I do think the odds are good the story I’ve laid out is at least part of the explanation. Did medieval and early modern users of manuscripts themselves recognize this stylistic divide? Did they think about and theorize it consciously? Unfortunately we just do not have a lot of self-reflective materials on scribal culture, though it is possible that in the works that do exist there is something on this topic. It is also possible that it was simply an unwritten rule of sorts, passed down in scribal chains of transmission; one wonders given that scribes did not always stick to their own confessional community when doing paid work whether individuals switched between styles depending on the confessional status of the text being copied.

One of the things I have learned over the course of working on manuscripts and devling more and more into the mechanics and dynamics of these works is that what can appear to us as mere aesthetic choices—script style, for instance—often had much more profound meaning for the people who originally made and used these items. Whole cosmologies and communal identities are frequently encoded into the visual aspects of these texts, and while recovering them can be quite tricky, it is always worthwhile to pay attention to such things and to try and make sense of them as best we can.