For a long while now I’ve been promising myself and my readers more in the way of autobiographical writing, specifically, an exploration of how I got to where I am spiritually, intellectually, and so forth. My life is not of great—or even minor!—historical import in the great scheme of things, but I do think that in its telling there are some interesting and useful things that can be discerned about the last four decades or so. Autobiography is always a rather presumptuous textual act, both in the assumption that one’s self-remembered life is worth recounting to others (hence the frequency of apologetic prefaces), and that one’s memories and narrative framing are trustworthy enough to impart some degree of historical (or otherwise) truth. All writing selects and even distorts to some extent, of course (though so does all sensory experience: one can only perceive and know so many things at once). But a sustained narrative is especially tricky, since it acts as if it has the perspective of Divine Providence, finding teleologies and intentions where in fact they probably were not present. Safer, perhaps, to assemble an account of one’s life from the ebb and flow of things, not always coherent, not always predictable.

So in lieu of—for now—sustained narratives of the Big Events in my life, I’d like to offer an occasional series of memories and reflections, specifically having to do with another of my current theoretical interests, the history of textuality and of ‘informational’ technologies more broadly. I do not think my childhood or teenage years were in many ways typical of the wider era—I was an odd kid living in relatively unusual milieus relative to the rest of America—but there are still points of intersection with wider historical patterns and with communities and ways of doing things that might not have been dominant but were still important during those decades (the 1990s and earliest 2000s). Over the course of my life the world has seen some quite major changes in the history of textuality, in how humans communicate and think and perceive the world.

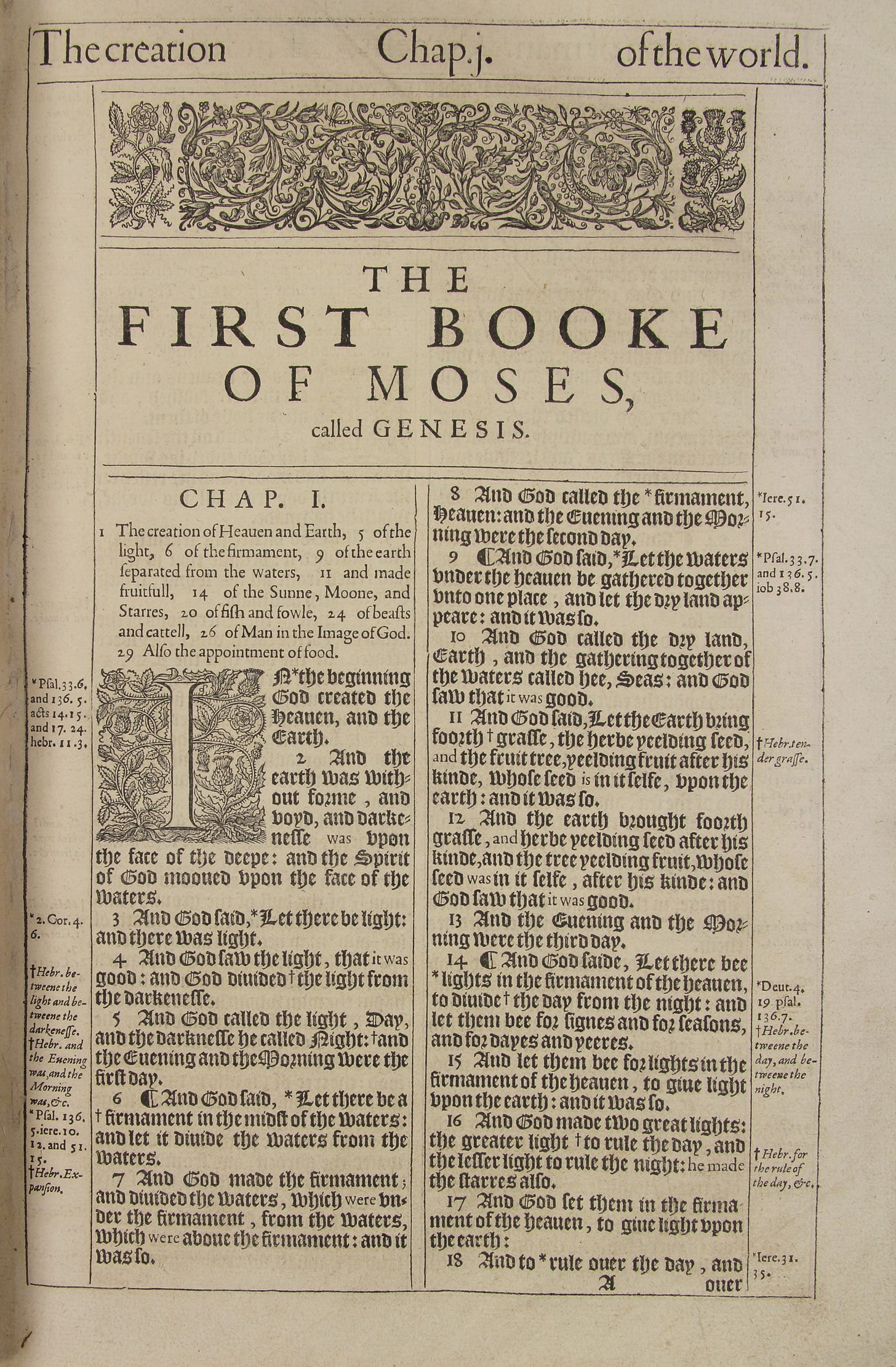

But if some of my reflections will intersect with the grand transformations of our time—the pervasive emergence of the digital, primarily—I want to start with a very niche example from my childhood, one that I imagine will strike anyone who did not grow up in a Southern evangelical (perhaps limited to specifically Southern Baptist and adjacent congregations) environment as downright weird, because, well, it kind of is. If you had to guess what ‘Bible drill’ is, you’d be correct if you conjured up an image of something vaguely military: as we practiced it, it involved a precentor giving out—barking out is actually pretty apt if my memory serves me correctly—either a specific Bible verse, a verse reference, or a theme which was attached to a specific verse. The drillers—children and young teens—would stand in a line shoulder to shoulder, with regulation—I’m not making this up!—size King James Version Bibles held at the waist, like swords (and it would seem that the late 19th to early 20th century ancestors of the modern practice were known as ‘sword drills’). Once the preceptor had finished giving the reference, the drillers had a set amount of time (ten seconds I think) to rapidly turn to the reference in question. This entailed being able to do, at minimum, two things: one, to have the appropriate verses and themes memorized adequately as to immediately recall the correct correspondences, and, two, to remember and be able to navigate to the correct location within one’s Bible. Location reached, the drillers put their fingers to the verse in question; I do not remember precisely how our correctness was evalulated, but the goal of the contest aspect was to be faster than everyone else. There were—and are—regional and I think even national (well, if you take the American South as a nation) level contests for Bible drillers who advanced through the proverbial ranks; I never made it to the national level, though I was pretty good.

If you too dear reader participated in this curious practice as a child you are no doubt either thinking back fondly or less fondly (Bible drill involved a lot of memorization, which is one of those things small children seem to do automatically but which becomes more laborious as one ages). If you did not grow up in a Bible drilling world, you’re probably thinking that this all sounds downright bizarre, and almost, I don’t know, irreverent. And yeah, I guess it kind of is—it’s certainly odd, and the mixture of gamification and the utilitarian handling of the physical copy of Scripture now strikes me as inappropriate at the very least. But I have not come to critique a relic of my evangelical childhood: instead I want to think about what it meant for me positively, as a way of interacting with the text of Scripture, the paramount Text in Christian cultures and a lodestone, along with the Torah and the Qur’an, for just about all alphabetic textuality of the last couple thousand years.

I wouldn’t say that I always loved Bible drill, though I do think I’d have done it even without parental encouragement. Certainly my memories of Bible drill are remarkably vivid: I can picture the rooms in which we praticed, the posture I took, how the Bible felt in my hand, the rush of searching my memory and translating it to my fingers furiously paging through the thin leaves of the little black Bible. Part of the appeal was that I did—and still do!—love Scripture, and enjoy the sheer tactile pleasure of leafing through a printed Bible, which in any iteration I’ve yet come across has a fluidity unlike almost any other book; I suspect that our regulation editions were made to facilitate that fluidity even more than other editions. Semantically, the multiplicity of the Bible, its aggregate nature, the strange and wondrous mixture of the familiar and the bizarre, the passages that are second nature and those that you’re pretty sure you’ve only ever read once, the comforting and the disturbing—as you move through it, even rapidly, it’s all there. Being able to rapidly navigate it, to know the ordering of the books, the (anachronistic, but certainly helpful) divisions of chapters and verses, these things helped to stabilize the text to a degree, but they also drew me into it with its weirdness and wonder. To be sure, the thematic headers given to the verses were designed to reinforce Baptist doctrinal commitments, sometimes in a decidedly tenuous manner, evident to me even as a child. Nonetheless, even such exegetical shaping encouraged, in me at least, thinking through those implications—was this an apt classification? Was this really what the Bible had to say about the topic?1 Already a disjuncture between the authority of the Text and the validity of the exegete was intruding upon my young mind, but that’s another story.

More concretely, Bible drill put great emphasis upong the physical nature of the book, it shaped a bodily relationship to the text, in posture, in the movement of one’s fingers, in the transaction between memory and limbs—in short, it was a sort of liturgical action, preceded by the ascetic discipline of memorization and physical navigation of the text, over and over again. This kind of rigor and bodily comportment is largely absent in other aspects of low-church Protestantism; outside of charismatic groups most evangelical services involve, at most, standing up a few times for hymns. If evangelicals claimed a high view of Scriptural authority, that did not translate into any particular relationship to the physical books themselves—unlike in Orthodox or Catholic Christianity, Baptists and other evangelical groups generally do not in any way venerate copies of Scripture, nor incorporate them into liturgical actions, other than occasional readings during services (often in the context of the sermon). Bible drill put the Book in dialogue with the body, no small thing in what was and is a markedly a-liturgical context. This almost liturgical aspect of Bible drill was, I guess, in a certain tension with the other thing that attracted me and no doubt other kids: the gamified aspect, the contest with my peers to, frankly, be the best. Now, in retrospect such gamification does not seem really appropriate, but I have to say it is hardly unique to modern Southern Baptists. Qur’anic memorization and recitation have been culturally valuable and even gamified skills for a very long time, to give an example from a history I know well. Indeed, a recurring theme in Islamic reformist critiques of their peers has long been the evils of Qur’an reciters who distorted the text into an object of artistic display. But that the core text of a community would enter into displays of virtuoisity and skill seems all but certain, and I don’t know that we should be too troubled by it.

On a somewhat different tack: when I started participating in Bible drill—at some point in the 1990s—the internet was a thing, but it wasn’t yet a big thing. Books were still firmly analogue, and while electronic texts did exist, their readers were probably even more niche than Southern kids doing Bible drill. I certainly turned to the early internet for information, but it was still in the form primarily of discrete articles and of databases (I fondly remember downloading what at the time seemed like massive JPEGs of NASA images from whatever space probes were then transmitting back to earth, our dialup would slowly resolve images of Io or some other distant world, the glacial unfolding of the image from top to bottom itself a sort of voyage of discovery). I do not remember when or what the first book I read entirely on the computer was, but it would have been at some point in the 2000s. Bible drill was, by contrast to what was to come, firmly analogue, and it was, as it turns out, excellent training for the skills needed to navigate textuality generally: the central activity during drill is that of search, of navigating a complex ‘library’ of books using the paratextual apparatus. These are not intuitive skills, but must be learned. Bible drill has stood me well in this regard, as an early and well-impressioned means of thinking and feeling a complex textual system, of finding what I was looking for. Such skills translate, imperfectly, into the digital world as well, but that’s another topic for another time.

Finally, and perhaps most crucially, Bible drill was for me a means of practicing the art of memory, and in that sense it stands well within a very long stream of practices within scriptural traditions. I certainly didn’t know it at the time, but the hours I spent memorizing pages of Scripture verses and drilling myself in their recall and in finding them in the text itself would have been perfectly recognizable to adherents of scriptural traditions stretching back over the last two thousand years; if by the 1990s in the wider world the importance of ‘rote’ memory was in steep decline, it remained important in my youthful cultural circles, unknowingly carrying on a very long tradition of engagment with sacred and significant text. Even the choice of the source text—the decidedly archaic KJV which by the 1990s was not the usual version in congregational worship in most places—was somewhat akin to much older traditions of a diglossic relationship with sacred texts. Now, the feats of memory upon which we were enjoined paled before that of Muslim memorizers of the Qur’an, or even of the typical medieval or early modern school-child in a Qur’anic school. Still, I memorized a decent chunk of Scripture, and retain much of it still. If my relationship to Scripture has changed in many ways over the last twenty or so years, that retention in my memory remains a genuine treasure, as does the skill of memorization itself.

Memory is the stuff of, for lack of a better word, wisdom; it is the ability to retain words, information, knowledge, textual references, the whole vast assembly, and to consciously and unconsciously assemble it all into new forms, apply it to new situations. Far from being a dead thing, the memorized text or fact or what have you is, properly taken, a tool, a resource, an almost endlessly plastic yet firmly fixed item with which the work of life in the world can be undertaken. One of the lessons of Bible drill is the relationship between memory and search: far from search and database replacing memory, they can and should fruitfully interact, with stores of memorized information and locations providing a map for search and navigation of the text. In our digital world such a combination of human memory and nimbleness of navigation is even more important than in the analogue world of the ‘90s; it is also harder to obtain and to retain, and I’m now a long ways out from childhood sessions of memorization and recitation. Yet the traces remain, for which I am glad, all the weirdness and problematic aspects of Bible drill aside.

I don’t remember when I last participated in Bible drill, probably around the turn of the millennium, so it’s been a while—yet despite the fact that Bible drill was not a huge use of my childhood time, it has genuinely left a deep impression, as I hope I’ve conveyed in the above. It’s a nice example of how an individual—in this case, me!—can simultaneously inhabit the ‘big streams’ of history (say, the rise of the internet) but also decidedly niche ones, which might even run (inadvertently, in the case of Bible drill) against the flow of those big streams. Obviously you can’t explain my scholarly career or later spiritual path solely in terms of my being a pretty good Bible driller—but that fact certainly has played a role, and I don’t know that I would have had the same scholarly and personal trajectory otherwise. Such are the ways of historical contingency and of Divine Providence!

If you’ve made it this far, you might be interested in the themes I’d like to cover in future weeks, such as:

the role of keeping notebooks in my childhood and teenage years

my precocious encounter with the research library

the weirdly prominent role of very specific paper ephemera in my self-fashioning

further encounters with Scripture and eventually with icons and liturgical texts

As in this essay, I hope to use snippets of autobiographical reflection to get at larger issues in the long history of textuality and of changes to information, knowledge systems, and self-fashioning and identity-making over the last thirty years. Comments would be especially welcome on these essays—did you do similar things in your youth? What institutional settings, practices, habits, technologies, shaped your relationship with texts, with information, knowledge, and so on?

I’ve occasionally thought about how fun it would be to do an ‘alternative’ version of Bible drill, selecting questions and answers that would not exactly fit in the milieu of my childhood, viz., Q. “What does God say about capitalism?” A. Isaiah 5:8: “Woe unto them that join house to house, that lay field to field, till there be no place, that they may be placed alone in the midst of the earth!”