Of Ancient Apocalypses

From Empty Ends of the World to the Great Eucatastrophe

i. It’s the end of the world again

When I first saw mention of the recent Netflix ‘documentary’ show Ancient Apocalypse, the showcase of fringe theorist Graham Hancock’s ideas about the ‘real’ origins of post-Pleistocene human civilization, I was mildly intrigued. I was vaguely familiar with Hancock, and while brief perusal of his arguments did not instill any confidence, the fact that his show would delve into the deep human past and attempt to incorporate it into a larger explanatory frame was interesting, especially once it became clear that a lot of people were watching this show. And so, somewhat against my better judgment, my long-suffering wife and I made our way through some of the episodes, a sufficient amount given that approximately half of each episode is just side-profile shots of Hancock looking either mildly pensive or mildly agrieved, with some important archeological site in the background.

For those who have avoided this minor cultural phenomenon, Hancock’s central motif is that a vast, Atlantis-like civilization existed towards the end of the Pleistocene, but it was completely—as in, every last trace of en situ evidence—wiped out by the events of the Younger Dryas climatic interregnum. More specifically, he claims that it was the alleged impact of extraterrestrial objects that triggered the climatic down-turn at the start of the Younger Dryas and so caused this apocalyptic disappearance. Confusingly, he blends the very real climatic down-turn1 with the later also very real but not simultaneous massive rise in sea levels as the brief return of the cold faded away and the ice resumed melting. This end-Pleistocene sea level rise washed away all of the Pleistocene Atlanteans, who, with perhaps one exception in Hancock’s mind, were brilliant but not brilliant enough to decamp a few miles up from the seashore. In the show’s telling, the certainly rapid—on a geological scale—sea level rise was akin to a massive global flood, albeit only affecting certain parts of the continental margins, but enough apparently to (convienently!) wipe out all traces of the alleged advanced civilization. The post-apocalyptic survivors—the ones smart enough to walk uphill or build some boats presumably—set out on a multi-century civilizing mission to the dimmer but dry hunter-gatherers up in the previously less desirable up-country closer to the ice, and in so doing instructed various peoples in building megaliths, earthworks, and all the rest (I’m pretty sure Hancock believes they instructed our ancestors in agriculture, but don’t quote me on that). Despite setting his apocalypse in the Younger Dryas, which took place some twelve thousand years ago, he somehow incorporates sites made over the next seven thousand years, in some cases disputing the accepted dates but often leaving the connections deliberately ambiguous. The show concludes with—well, we’ll get to that below.

In the month or so since its release, the show has attracted a range of commentary, most of it lining up with culture war positions (somewhat bizarrely, as there is precious little substantial political positioning in the show beyond vaguely liberal boilerplate—though Hancock seems to be cultivating right-wing audiences online in other ways). As I was thinking about how I might address this minor cultural phenomena at the intersections of deep history, popular entertainment, culture war politics, and epistemic conflict, it hit me that the obvious route would be to explore more seriously the ‘apocalypse’ angle—what might we learn if we tried to understand Hancock as a type of apocalyptic theorist in the grand old tradition of such beliefs and movements in the modern world, albeit, as we’ll see, with important differences compared to other, older apocalyptic and epistemically fringe movements of modernity.

Apocalypticism is a notoriously vague term, along with millenarianism, and rather like the predicted dates for the temporal world’s imminent consumption in fire or new transformational vibes, it can be nudged and fudged and distended. Of interest to us here is the way in which apocalyptic ideas with deep genealogical roots in Christian eschatology (even if the particular ‘sprouts’ usually came up far afield of the trunk of orthodoxy!) have often been transferred laterally into ‘secular’ or alternative religious contexts over the last two centuries, with or without claims of divine inspiration. In an ironic iteration of the tendency of modernity to dismember and isolate once holistic elements, many of the motifs and motivations and narrative styles of the ‘classic’ apocalyptic have spun off into other areas and purposes, into narratives and theories that draw upon the apocalyptic but do not necessarily check off all of the usual boxes.

For Graham Hancock, as for any number of ‘secular’ apocalypticists and related ‘fringe’ theorists, a postulated past apocalypse serves to bring together otherwise disparate places and periods of history, in a way that has more power than, say, simply seeing them all as a part of one vast and complex human story that refuses simple answers or narrative reductions (and yes, ideological systems and tendencies are not unrelated to the apocalyptic!). Apocalypticism, as well as various ‘fringe’ theories of history and cosmology (ancient aliens, New Age beliefs, young earth creationism, flat earthism, to name a few) more generally, not only seek to bring together the vast and disparate points of knowledge and data bequeathed by modernity, but these movements and theologies also look to re-instill a sense of unitive deeper meaning that has so often suffered in the aftermath of modernity’s disruptions, be it declines in religious faith, alienation from nature and the body, fragmentation of identity, experience, and so forth. Not only does the special body of knowledge about the ‘real’ origins of the universe and its imminent conclusion make sense of everything, the participant is given a roadmap of how to live in light of such knowledge, and not just to live but to live—for as long as the epistemic grounding holds out—meaningfully. The apocalypse or the fringe theory brings it all together, and reduces the overwhelming scale of a massive and massively old universe, of a human past that stretches deep into time and covers an almost unimaginable array of places and peoples in its full sweep. Every dot on the map is connected, and the dots form an arrow pointing to a final conclusion to which a date, exact or proximate, can be assigned.

What is striking, then, about Hancock’s apocalypse and his articulation of a body of ‘secret’ knowledge rejected by the clerisy is just how little profound meaning or metaphysical insight he claims to convey. His ideas are actually rather, well, boring when you think about them for a bit—we’re not told how precisely his advanced late Paleolithic globe-spanning civilization came about, though presumably it was de novo itself, unless he wants to posit a turtles all the way down scenario of sages from lost cities constantly emerging from the fiery mists of Pleistocene apocalypse to re-ignite the fires of civilization, handed to them originally no doubt by space aliens or something—but he does not, so far as I can tell. Nor does his apocalypse really have any profound inner meaning, it is only a spur, in his telling, to later myths, which he doesn’t just misrepresent by rearranging the details but which he fundamentally misunderstands by stripping them of their metaphysical and theological groundings and purposes. Myths and legends and traces of ritual and rite and devotion become in his hands prosaic and utilitarian warnings about deadly comets; the series ends, not with a call to repentance and spiritual renewal, but with the warning that civilization could get clobbered—again—by asteroids or comets or something ominous from space. If he hadn’t spent all the episodes denigrating all other experts and institutions it wouldn’t have been surprising if he’d issued a call for increasing the budget of NASA. There it ends—the apocalypse and the quasi-gnostic knowledge the viewer is made privy to doesn’t actually lead anywhere, it makes no great difference one way or another. It’s most assuredly not life-changing stuff, even if Joe Rogan’s mind was blown in the process.

Perhaps it is unsurprising then that more than anything else the show and its ideas have simply become—weird, to be sure—grist for our interminable culture wars, with progressives raising alarms, naturally, about racism and white colonialism and whatever other dangers they can conceivably work into Hancock’s mostly a-ideological ramblings. Meanwhile, rightists, probably largely in reaction to leftist condemnation, have latched onto it as a bold example of persecuted ‘forbidden knowledge’ that ‘they’ don’t want you to watch, presenting Hancock as a noble martyr (albeit with a cozy Netflix deal!) to the main enemy du jour, ‘wokeism.’ The dynamics are not very surprising, frankly, though it is notable that so many ‘conservatives’ would be completely comfortable with Hancock’s assuredly secular apocalypse, one that might make motions towards Biblical stories but which is definitely not a product of young earth creationism or any form of religious sensibility at all. It’s easy to overstate the ‘post-religious’ nature of the modern right, but instances such as this demonstrate that there is certainly something to such a shift, much as it’s significant that so many establishment voices foregrounded, less the absurdity of Hancock’s theories, and more the presumed (moral) ‘harm’ they did or the (also moral) ‘danger’ they entailed to the minds of credulous viewers and the presumed reflection of moral and political transgression those viewers are likely to embrace.

ii. context and meaning, or the lack thereof

To sum up, we might say that Ancient Apocalypse and its viewer responses represent a cultural moment that taps into our collective yearning for apocalyptic certainty with its potent meaning-making possibilities and its epistemic structuring of disparate facts and ideas, for its sense of finality, all revealed to a wise and far-seeing elect untroubled by the jealous condemnation of the clerical class and their moralizing and gate-keeping. So far, so good: we could be describing all manner of movements and theologies of the last five hundred years. What is striking is what comes after, as it were, and what is not included: the great wisdom of the ancient sages is purely utilitarian, the ancient monuments of the Neolithic they supposedly oversaw or otherwise influenced re-imagined as a globally distributed warning system written in code to appraise later generations of extra-terrestrial threats. The world-ending at the core of the argument isn’t even a total apocalypse, leaving the lowly hunter-gather types scot-free it would seem, ready to receive the wisdom of the past ages and get down to building modern civilization.

I’d go so far as to say that a lot of the left-wing concerns over this show are overblown if not utterly meaningless: what any of Hancock’s theories actually mean for us in the present day is left very vague indeed, foreclosing prescriptions for action or further interpretation good or bad. Perhaps it would be nice to find new sages, though given Hancock’s hostility towards authority figures and scholarly process, it’s hard to imagine him submitting himself to any body of knowledge or authority. In the end there is a constant hinting at deeper meaning, at more profound interpretations, but nothing is forthcoming. Just watch out for rogue comets, which on reflection isn’t really something we needed late Paleolithic shipwrecked sages to tell us is it?

It is interesting—and I am not the first to do so—to compare Hancock’s approach to another recent, and surprisingly popular, revisionist take on the Paleolithic and afterwards. David Graeber and David Wengrow’s book The Dawn of Everything re-examines the deep human past (well, the last twenty thousand years or so anyway) with an eye towards locating a greater and largely unobserved (by archeologists, historians, and the rest of our sorry lot) truths revealed in that past, truths that can guide future political iterations of human society. Now, don’t get me wrong, in most respects it is almost the exact opposite of Hancock’s theories: Graeber and Wengrow deliberately push against unitary theories of civilization evolution and the rise of the state, with the sheer diversity of human social arrangements and the implicit possibilities therein the central thrust of the book, the argument that structures the vast swathe of history covered, from the Paleolithic to the near-present. The coincidence is subtle: certainly, Graeber and Wengrow indulge a bit in playing the solitary and noble opposition, expressing surprise and shock at conventional archeologists and historians overlooking or misrepresenting various aspects of human political history.

But there is a great difference between arguing that we should give greater weight to the radical political possibilities revealed (by ordinary archeologists working in standard ways) in a site like Göbekli Tepe, versus arguing that the site actually contains in encoded form the secret knowledge of refuge sages from a Paleolithic mega-civilization wiped out in the Younger Dryas apocalypse. Graeber and Wengrow are certainly interested in convergences (what apocalypticists and fringe thinkers tend to mis-intepret as direct influence or coordination), but what really ties their narrative together are the divergences, the places where local histories move in unexpected directions. If there is a sort of unifying apocalyptic point (or tendency, they would reject identifying a single period or point in history as the defining moment or period), it is much closer to the present: the condition of ‘being stuck’ in oppressive, anti-liberatory political structures, though while their appraisal is naturally rather gloomy, the evidence of the past argues, or so they contend, that our current trajectory is not inevitable—though how precisely we are to synthesize their findings into political action is not clear. We are back at the conundrum of history without clear meaning, of history unable to serve as a cogent guide, whether the past has been massively overdetermined through the prism of recycled Atlantis theories and impact apocalypse or through the prism of a radically open and experimental deep human past with great promise but indeterminate and rather doubtfully practical prescription for the future.

iii. the Christmas connection, or, the only apocalypse that matters

All the angels in heaven make merry and dance today!

All creation leaps for joy!

The Lord and Savior is born in Bethlehem!

Every deception of idols is swept away,

And Christ reigns unto all ages!

Today the Virgin gives birth to the Maker of all!

Eden offers a cave.

To those in darkness, a star reveals Christ, the Sun!

Wise Men are enlightened by faith and worship with gifts.

Shepherds behold the wonder, and the angels sing:

“Glory to God in the highest!”

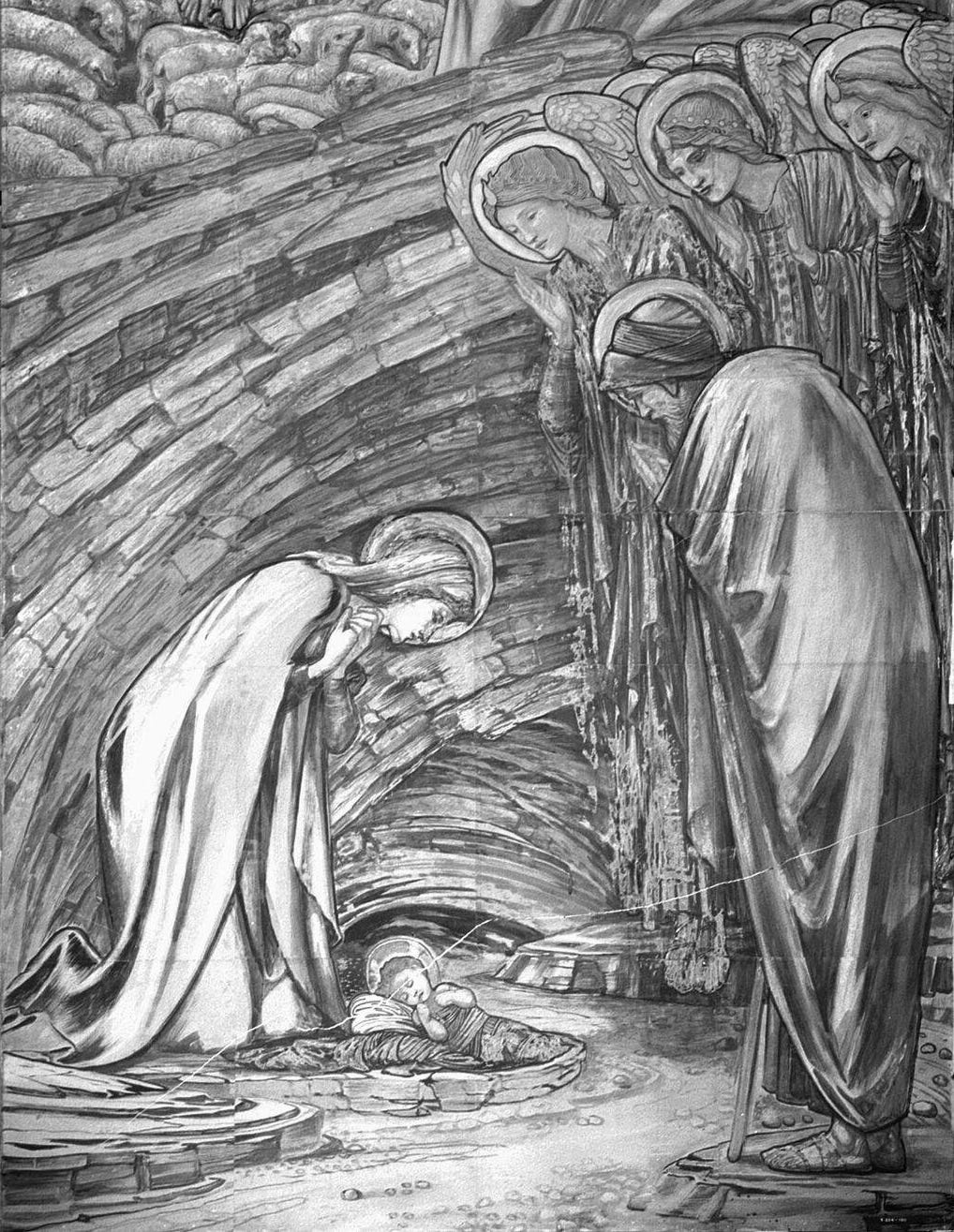

Litiya of the Nativity VigilToday is the day after the Feast of the Nativity, the great liturgical blaze of light in the depths of winter darkness, at once in continuity with millennia of human ritual and community across much of the northern half of the world, while also marking a rupture and a transformation of the old ways and old rites of winter. Our celebration is fundamentally about a specific moment in human history, a moment that is in a very profound way the most truly apocalyptic of all, even as it had none of the world-ending splendour and terror that we associated with the term. There is no geological record of the apocalypse of the Incarnation, and while we now divide our reckoning of human time at the juncture point of Christ’s Birth, that Birth cannot be detected by other more conventional historical signals such as changes in metal production or the rise or fall of some emperor or empire.

To be sure, in the long run of things the historical signal becomes quite strong indeed, but while the march of Christianity through human history is part of the story, it is only part, and the full meaning of the apocalypse of the Nativity, the eucatastrophe of the Incarnation, remains hidden in the workings of time, present, future, and past. Much as Christ’s Kingdom was not what His first century audiences quite had in mind, the apocalypse, the eucatastrophe that is His coming into the world of human history does not have the special effects budget, as it were, that we tend to want, nor does it mark a moment of finality in the sense of a literal, physical consuming end of the world. Yet it is not just an ending, it is the ending, the consumation of the ages before, and after, the verdict against the empires and kingdoms and systems of the world, the justification of the saints and true sages and spiritually adapt of ages past, from the Prophets of ancient Israel to the far-off seers and seekers whose traces remain in Paleolithic caves and archeological sites. The deep-knowing sages make their entrace into this drama, bringing their gifts, but they come seeking Wisdom, not handing it down to the masses.

Christians have been telling and re-telling this story, living and enacting it, for twenty centuries, with each generation realizing something somewhat different, manifesting the meaning and power of Christ’s gentle and hidden apocalypse for successive ages—becoming part of the story, part of the eucatastrophe, as we move towards whatever ultimate consumation further down the march of time. What I want to suggest in closing this Christmas exploration of deep time and present culture is that part of the task in the twenty-first century that we who are believers in this great and awesome Eucatastrophe is one of not meaning-making, but rather to take hold of the meaning we have been offered and within which we strive to dwell, and the weave it into the histories and encounters and understandings to which we in this moment of human history are privy. We ought to ask ourselves seriously what it means to see Christ—the Lamb slain from the foundations of the world—in the records of deep time, in the traces and intimations of human culture and society in the far past. A poetic theological imagination is called for here, I think, akin to the explorations of poetic theology we see in the ancient and medieval hymns of the Christian liturgy, East and West.

If we are to extend the implications of Christ’s great and dread Eucatastrophe, His hidden and shattering apocalypse, forward and backwards in time and into the fractures and folds of our own present and perilous anthropogene, we must take seriously both the datum of scientific investigation as well as that of theology and Scripture and liturgical imagination and contemplation. The cave of the Nativity—the strata of divine providence slowly unfolding in the layers of earth’s depths, their Architect and Sustainer, the love that contains the teeming denizens of Cretaceous seas and the hearts of humans in an age of alienation alike, brought out into the full force of time’s stream within their recesses. Caves are, to put it mildly, deeply resonant across the course of the deep human past. History is born in them, sheltering, containing, preceding the proud elevations of urban and imperial civilization, and here in the Nativity a cave embraces the true beginning and end point of history in the Person of Christ Incarnate as He is born into history. I do not think any of this is coincidental, but the convergence, the typology if you will, is a matter of mystery, of the inner working of the Spirit, not of some secret work of coordination by some ancient elite, say.

That is but an outline—really what I have in mind is precisely the original spur to this writing project, the juxtaposition of deep time and of doxology, of not just attempting some ‘reconciliation’ of ‘science and religion,’ but of something, dare I say, more profound, of feeling out and tracing meaning and praise of God in the archives of the past and the structure and dynamics of earth’s history and present, as prior to any more utilitarian end (and to be sure, our response to climatic crisis, to the deformations of industrial capitalism, and so forth, ough to be filtered through the priors of theological engagement and of doxological worship and understanding). Seeing the Gospel, as it were, in the structure of the cosmos and the depths of human history does not mean finding a road map that suddenly ties everything together and obviates the complexity and messiness of things; it is not an apocalypse in the conventional sense. It is an act of mystical knowledge in the true sense—not a source of some secret wisdom about the ‘true’ origin of things, passed down by hooded sages, but an awareness and celebration of the hidden inner meaning of things, beyond human knowing, expressed in the poetic and devotional. The message, the meaning, goes to the very purpose and fundaments of the cosmos, of geological time, of biological evolution, of human society and culture and all the rest; it is not a matter of easy formulas or solutions, to be sure, but it is a message of hope, hope in the deepest and most substantial form.

Let me end with an excerpt from a poetic work that perhaps more than any other exemplifies just the sort of synthesis, the vision I’ve in mind, a joyful and artistically brilliant encompassing of all things past and present in the illumination of Christ, the Welsh high modernist poet David Jones’ The Anathemata,2 here exploring ‘types’ of the Theotokos and of the Eucharist in Paleolithic art:

But already he’s at it

the form-making proto-maker

busy at the fecund image of her.

Chthonic? why yes

but mother of us.

Then it is these abundant ubera, here, under the species of worked lime-rock, that gave suck to the lord? She that they already venerate (what other could they?)

her we declare?

Who else?

And see how they run, the juxtaposed forms, brighting the vaults of Lascaux; how the linear is wedded to volume, how they do, within, in an unbloody manner, under the forms of brown haematite and black manganese on the graved lime-face, what is done, without,

far on the windy tundra

at the kill

that the kindred may have life.

How this sort of vision can be conveyed in other ways and to wider audiences (there will never be a Netflix adaptation of The Anathemata!) is another question for another time, and this essay has already grown far beyond my original intention of commenting on the intersect of deep history, fringe theories, and the culture wars. In the new year, God willing, I hope to explore these things more, in particular just what and how this meeting of deep time and doxology might shape our relationship to one another, to the land, and to our lives here on earth in our particular historical circumstances. Until then, may you have a blessed Christmas season, and a happy New Year!

Some people have indeed argued the Younger Dryas climatic deterioriation was caused by an impact event but the majority of observers continue to contend that it was much more likely precipitated by the sudden in-rush of cold melt waters from the retreating North American ice mass; while impact events do happen, it is worth noting that the only really firmly established ‘apocalyptic’ such event remains the end-Cretaceous one.

pp. 59-60; the note that Jones apends to this section is worth reproducing here, as it is most apropos to the ideas I’ve been developing: T’'he findings of the physical sciences are necessarily mutable and change with fresh evidence or with fresh interpretation of the same evidence. This is an important point to remember with regard to the whole of this section of my text where I employ ideas based on more or less current interpretations of archaeological and anthropological data. Such interpretations, of whatever degree of probability, remain hypothetical. The layman can but employ for his own purposes the pattern available during his lifetime. The poet in c. 1200 could make good use of a current supposition that a hill in Palestine was the centre of the world. The poet of the seventeenth-century could make use of the notion of gravitational pull. The abiding truth behind those two notions would now, in both cases (I am told), be differently expressed. But the poet, of whatever century, is concerned only with how he can use a current notion to express a permanent mythus.’