Of Holy Wells and Raw Water Enthusiasts

Or, When Water is More than Water

In an age in which we in the ‘developed’ world have grown completely used to water coming from taps, the precise process of delivery perhaps a bit opaque given how little we generally have cause to contemplate it, it might seem that springs of water—naturally occurring points at which water issues suddenly from the earth—would hold considerably less charge in our imaginations. Certainly, it is hard to appreciate emotionally now the vitality of reliable, generally safe water sources in places without industrial-age water supply—much like our relationship to light and darkness there has been a very fundamental reconfiguration that we can only recover through deliberate choice. The mythical and mystical and sacramental aspects of sources of water, once widespread globally and reflected in liturgical observance, popular practice, shamanic ritual, have largely receded in importance and visibility. And yet—springs of all sorts, whether still holding prior cultural overtones or not, retain a certain power and mystery, an attraction, that has proven hard to shake.

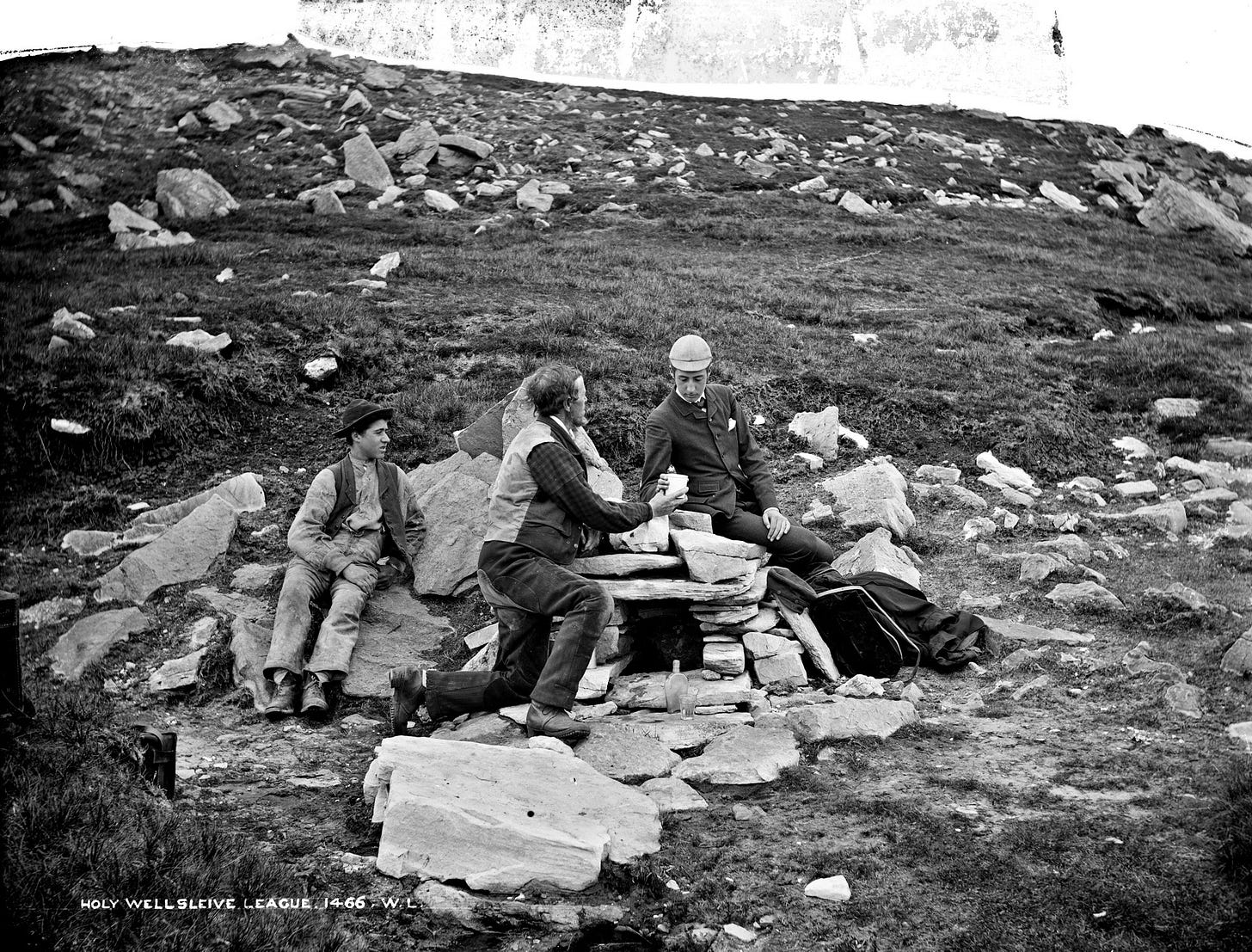

There is I think something just fundamentally fascinating about springs, far beyond their practical utility, a fascination and collective cultural understanding that has developed seemingly autonomously again and again across human history. For the Indigenous peoples of the American South, as well as for many peoples across the world, springs represented contact points between the lower world of the spirits and this world, portals to other realms and powers. The springs of the karst South—especially abundant at the contact point of mountain and valley floor—are indeed numinous feeling places, entire streams and rivers issuing forth full-formed from within the bosom of the earth. Sometimes human passage into their issuing caverns is possible, but as often as not it isn’t, intensifying the mystery. Yet even rather meager flows of water have historically taken on great significance—witness the holy wells of Ireland and many other regions, sometimes barely a trickle, yet possessed of centuries, if not millennia, of layered significance and association with holy beings and powers. The cases of a holy spring of Orthodox Constantinople, the Zoödochos Pege pictured in the icon above, and of its more explicitly Islamic ‘competitor’ spring discovered nearby after the Ottoman conquest of the city, the Merkez Efendi Ayazma, are good examples of this layered complexity, of the mixture of the ‘inherent’ charge and power of these features with theological interpretation. In both cases (which I have described in more detail here: A Tale of Two Holy Wells) the sacred sources of water are described as speaking from within the earth, as if they were themselves persons with lives of their own. And indeed one of the consistent features of springs—sometimes to great human frustration, sometimes to great delight—is their dynamic quality, which can involve odd patterns, shifts in hydrology, unusual chemical compositions, and so forth, adding further to their cultural power.

All of this historical background is to preface my discussion of a contemporary emergent trend here in the United States of people collectively seeking out springs for purposes of drinking water—‘raw water,’ on analogy to the related (though not exactly conterminous) trend of ‘raw milk’ enthusiasm. As someone who spends more time on Twitter than is healthy (though I’m not sure any amount of time is actually healthy) I was vaguely aware of ‘raw water’ boosters. The movement has grown enough to attract coverage recently in the New York Times: ‘Raw Water’ Devotees Swear by Natural Springs, Despite the Risks. The article takes as its centerpiece a spring in California, the Red Rock Spring, recording reactions from users and their ritual practices:

“Vibrations for the soul,” one visitor wrote. “Pure water pure magic,” wrote another.

In South Carolina, vendors sell fresh watermelon, oranges and pecans behind a rural church near Blackville where people flock to collect water from two spigots in the ground. On any given day, you’ll see spring water believers crouching to fill giant bottles at the headwaters of the Sacramento River in the northern reaches of California. In rural Oklahoma, people drive hours to draw from a natural well along the highway thought to contain healing liquid…

Acolytes in the self-proclaimed “Red Rock Spring cult” have planted squash, tomatoes and other vegetables nearby, and built an altar where people leave tokens of gratitude on the rust-colored mountainside: a stack of nickels, a dried flower crown, fresh figs, a marijuana joint.

Unfortunately the authors of this article did not provide the kind of historical and anthropological background that would help to make some more sense of these sorts of reactions. For that I don’t really fault them—it’s much easier to figure out which experts to contact if you want to know about the safety of untreated water, say, than to find someone well versed in the history of holy wells. But—to digress a bit—the range of expertise cited in the article gets at a very fundamental problem with so much of ‘expert culture’ and its interface with public policy, journalism, and the like: technical, hard scientific proficiency abounds, but the grounding, insight, and, yes, complication of things that can be offered by scholars in the humanities often go missing. Don’t get me wrong—public health expertise is important here, and there are genuine concerns when it comes to the general public obtaining water from springs which ought to be addressed; but to do so productively additional understanding and perspectives need to be centered too.

But to return to our subject at hand. What is so striking here is that the examples described really have very little to do with one another, and cannot be reduced to recent trends around all things ‘raw’ (which is itself a politically and culturally complex, and often quite weird, trend or group of trends). For instance, the holy spring in South Carolina—God's Acre Healing Springs—has a genealogy going back quite likely to the eighteenth century, and has developed over the last century and a half or so its own cult of veneration—this despite being in a part of the South that is not just Protestant but quite solidly Baptist, the spring having a Baptist church right next door. It is pretty unlikely that most of the people who have shaped its cultus (including the solemn deeding of the whole place in the 1940s to ‘ALMIGHTY GOD’) are at all aware of similar traditions in other places. Nor does it strike me as likely that the ‘acolytes’ of the Red Rock Spring were consciously trying to imitate the traditions of historical spring devotees—their depositing of votive offerings perhaps simply made sense somehow to visitors.

Holy springs are often places with long histories of veneration, and as such have often been interpreted as evidence of ‘survivals’ of more ancient religions and cults, with Christian or Islamic or other belief systems rather precariously wedded to them later on. Perhaps in some cases there is indeed a grain of truth to such arguments, but just from the examples above it should be clear that as often as not ‘cults’ of springs and holy wells emerge not just on their own without prior precedent but even against the grain of prevailing ideological systems. At some level I wonder whether there is indeed something ‘inherent’ in the power of these topographical features, a resonance that is picked up across human time and space regardless of other cultural and even material contexts. But that is not enough on its own: every tradition of holy water sources, of water becoming more than water, is formed by particular historical circumstances and forces, including reactions against and resistance towards societal forces and constructions.

In the case of modern American springs, there are several things going on simultaneously, the importance of each varying from place to place and even person to person. A general dissatisfaction and even distrust of industrial capitalism—whether expressed in such terms or not—is widespread, and lies behind, however inchoately, many trends. Humans need narratives, spatially and materially congealed forms of meaning, and concrete social connection, all things that systems of mass anonymized production tend to lack, or even rigorously mitigate against. A spring as a water source provides a concrete sense of place, of community—the people who together visit the spring and carry away its waters for personal use—and of meaning, potentially multiple layers of meaning and significance, especially in the contemporary world within which there are few widely shared cultural referents. More deeply, because they are dynamic, often personified, places, springs feel alive, like agency-possessing beings, and as such transfer, osmosis like, a sense of agency to their users, in a way that turning on the tap simply cannot do.

Of course there is still more going on, from beliefs about divine intervention to conspiracy theories to mere convenience in some cases; it is the mutual convergence of all of these dynamics that matters. And crucially springs, whether imbued with holy or healing or mystical qualities or not, almost always function as a type of commons, even when legal recognition and social legibility of commons practices have largely disappeared. Roadside springs like the Red Rock Spring above are an excellent example: they are outposts of nature that do not fall under either private or state ownership or management, the community of use around them emerging more or less spontaneously and in true decentralized fashion. And even if people lack the language to describe such a model, the social nature of it feels right, despite the cultural and political baggage of ideological formation we all carry in regard to ownership and use. This desire to recognize water as more than mere water, and to understand it within a shared social frame, could be applied to more modern and automated sources of water, but that is a discussion for another time.

Monday was, for Orthodox Christians on the New Calendar anyway, the feast of Theophany (though we celebrated in our parish on Sunday, and will do the Great Blessing of the Waters this coming Sunday, weather permitting!), the feast commemorating, on the surface anyway, the Baptism of Christ in the waters of the Jordan River. But listen to the hymns and Scripture readings of the feast for more than a moment and it becomes clear that the feast has a much deeper significance, starting with the name: it is the Theophany, the revelation of the Triune God at the hands of St. John the Forerunner and through the waters of the Jordan River. The water of the river, and by extension all waters, are treated not as accidental elements in the Theophany, but as part of the point: we speak of the sanctification of water as an element, of the power of the Lord’s Baptism coursing through all bodies and sources of water on earth. And we bless water liturgically, both within the space of the church—it is as if we temporarily have our own holy springs set up—and without. Perhaps we can speak of a continuum of sacredness, the numinous spring or well that is well nigh universal in human culture the sporadic sign and presence of the holy potential of water, with Christ’s transformation and sanctification of the waters of the world in His Baptism a fulfillment and universalization of the potential of water, that substance most vital for life, even more so than our planet’s other great treasures, having preceded oxygen by billions of years.

Well. I have only scratched—dived into perhaps—the surface of this topic; I hope to return to it over the coming months, perhaps in a manner analogous to my earlier treatment of night and darkness, so watch this space to see what comes to the surface in the coming year.