i. technologies of keeping time

Time and technology are two continually intertwined entities, if that’s the right word, in ways that are often so pervasive that we fail to recognize them at all. Some of them are, on a little reflection, obvious: think of clocks, calendars, and the like. Lying behind them are technologies of observation and prediction, the steadily accumulated applied knowledge that allowed us to predict with pin-point accuracy this week’s eclipse, for instance. Time past can be measured, with varying degrees of precision, precision that has steadily increased over the last century. But at the level of direct application, of how we divy up daily and yearly time (including what counts as a ‘day’ and what counts as a ‘year’), how we picture our relationship to time past and time future—those are all dependent upon fundamentally social technologies, conventions that intersect with in meaningful ways but are not simple reflections of the passages of time that they seek to make culturally legible and useful.

Just at the level of the ‘ordinary,’ (literally) quotidian passage of time, the social technologies humans have employed over our history have varied greatly, both in terms of how the time of days and years is divided up and measured, and in terms of what those cyclical passages of time mean, what, if any, significance particular points in the calendar might have. What has been close to universal is the human fascination with the passage of time, and our insistence on interpreting it, of making meaning—social, cultural, religious, what have you—out of that passage and the meaningful units into which we divide it and relate it to our perpetual present in which we live. It is not much of a surprise that the handful of surviving Maya codices that have come down to the present, for instance, have to do with the measurement and interpretation of time and its intricate demarcation within the Maya calendar system, demarcations that Maya daykeepers hoped to employ for prognostication of the future (which in a way was as ‘written’ as was the past).

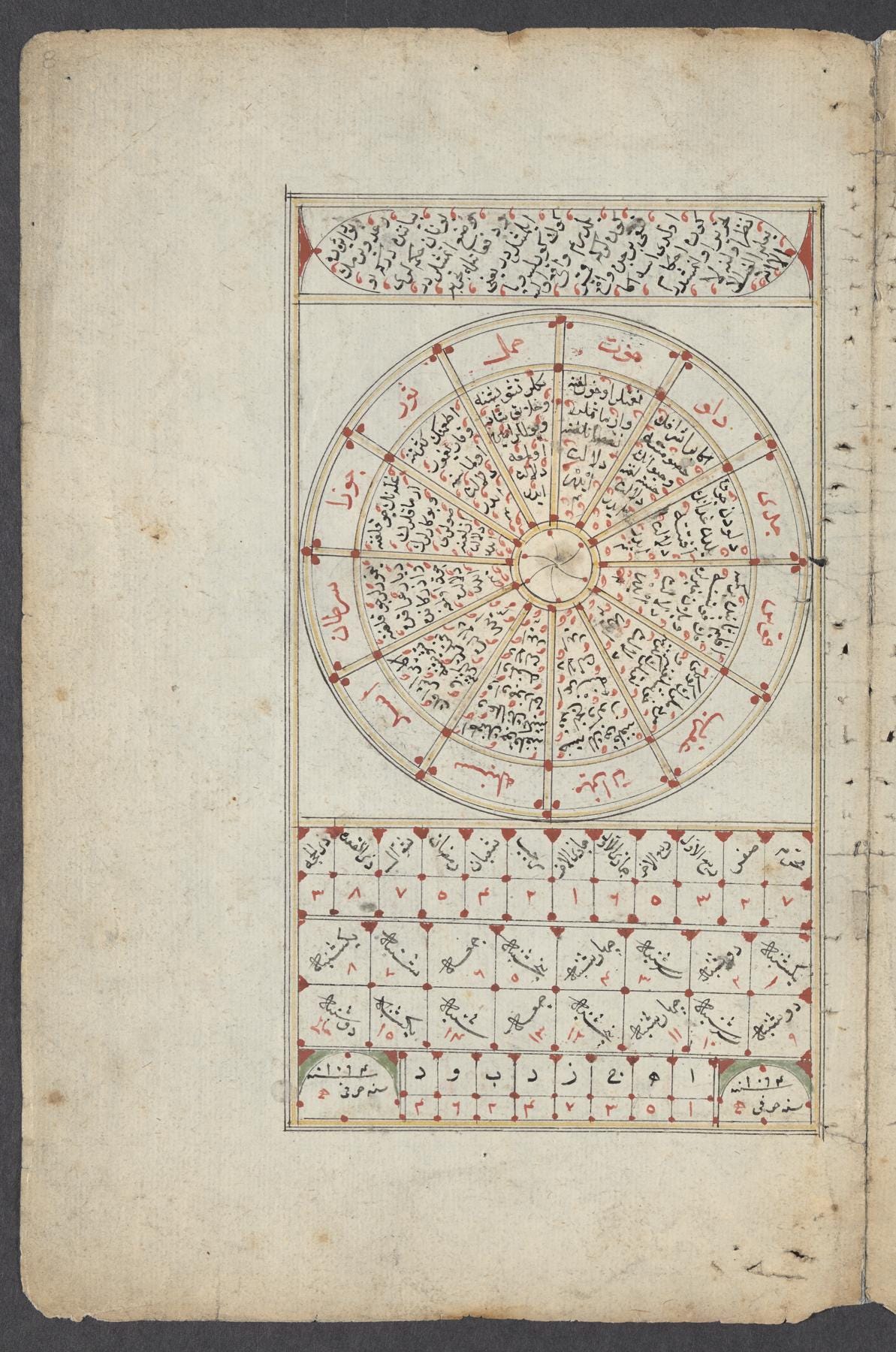

Yet if the division of time into cycles of k’atuns with complex modes of finding a specific day’s date are an exceptionally complex manifestation of the human proclivity to measure and give meaning to time, the basic form of the manuscript above is comensurable with medieval and early modern examplars from the other side of the Atlantic; compare the tables of texts and numbers in the Maya codex above to the charts in the following page from a 17th century Ottoman Turkish calendar and guide to the zodiac:

While there are obvious vital differences between the two, what is remarkable are the points of convergence, both in content—both are shaped by a convinction that cosmic cycles of time intersect with and shape human history, and are predictable—and in form, right down to the mutual rubrication of numbers. Despite the fact that the two cultures represented here are separated by, at the very least, some twenty thousand years, both were simultaneously producing books treating the demarcation and interpretion of time, using broadly similar epistemic technologies to do so. It’s a little dizzying to think about—in part because I have my own suite of technologies with which to frame this example of human cultural convergence, which might not have been quite so dizzyingly impressive to an early modern observer. My perceptions are filtered through the lenses provided by the ‘discovery of deep time,’ and the epistemic tools through which I can visualize the vast chronological period of divergence separating Mesoamerican scribes from Ottoman Turkish ones.

ii. a brief history of the universal history chart

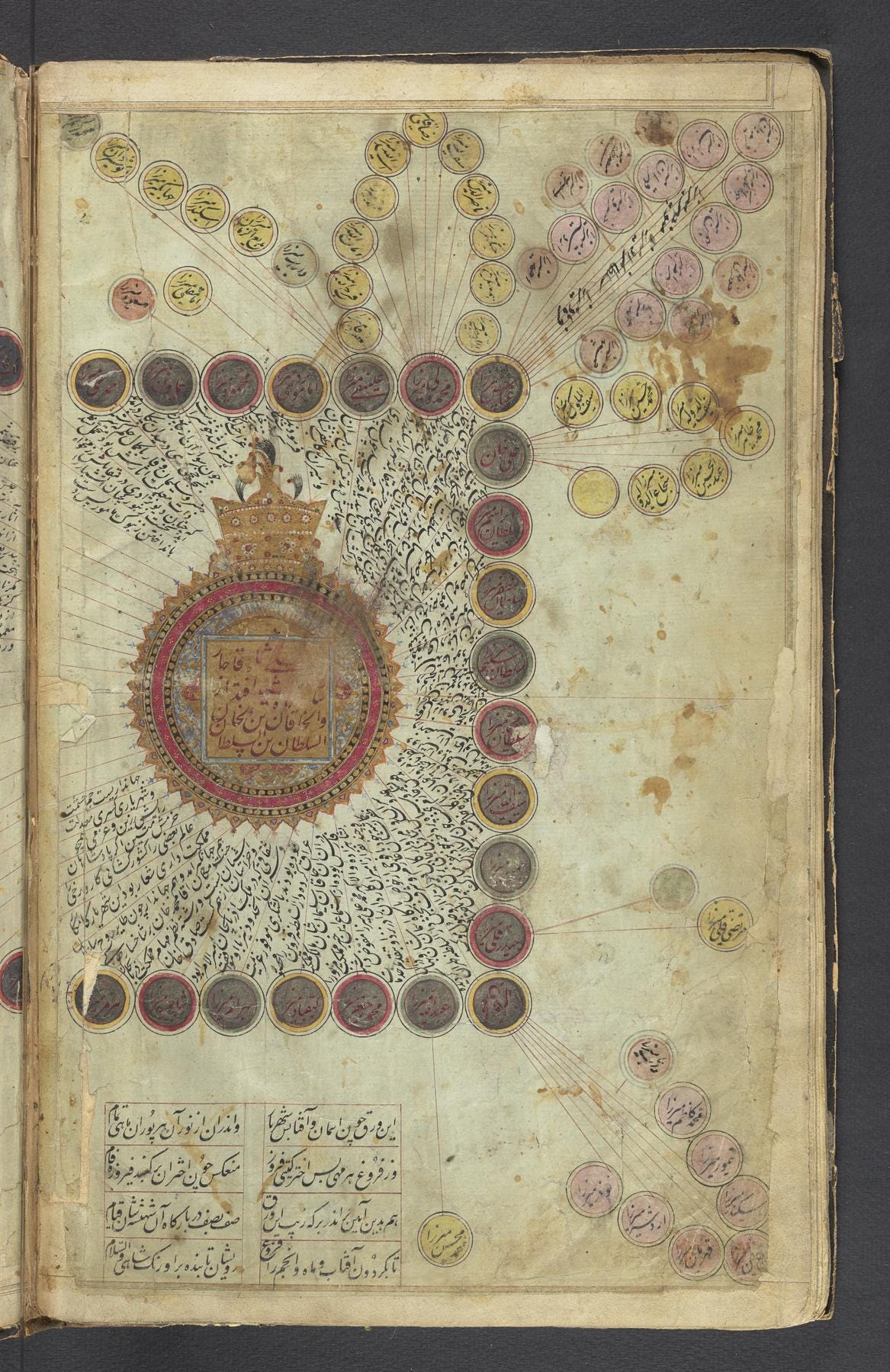

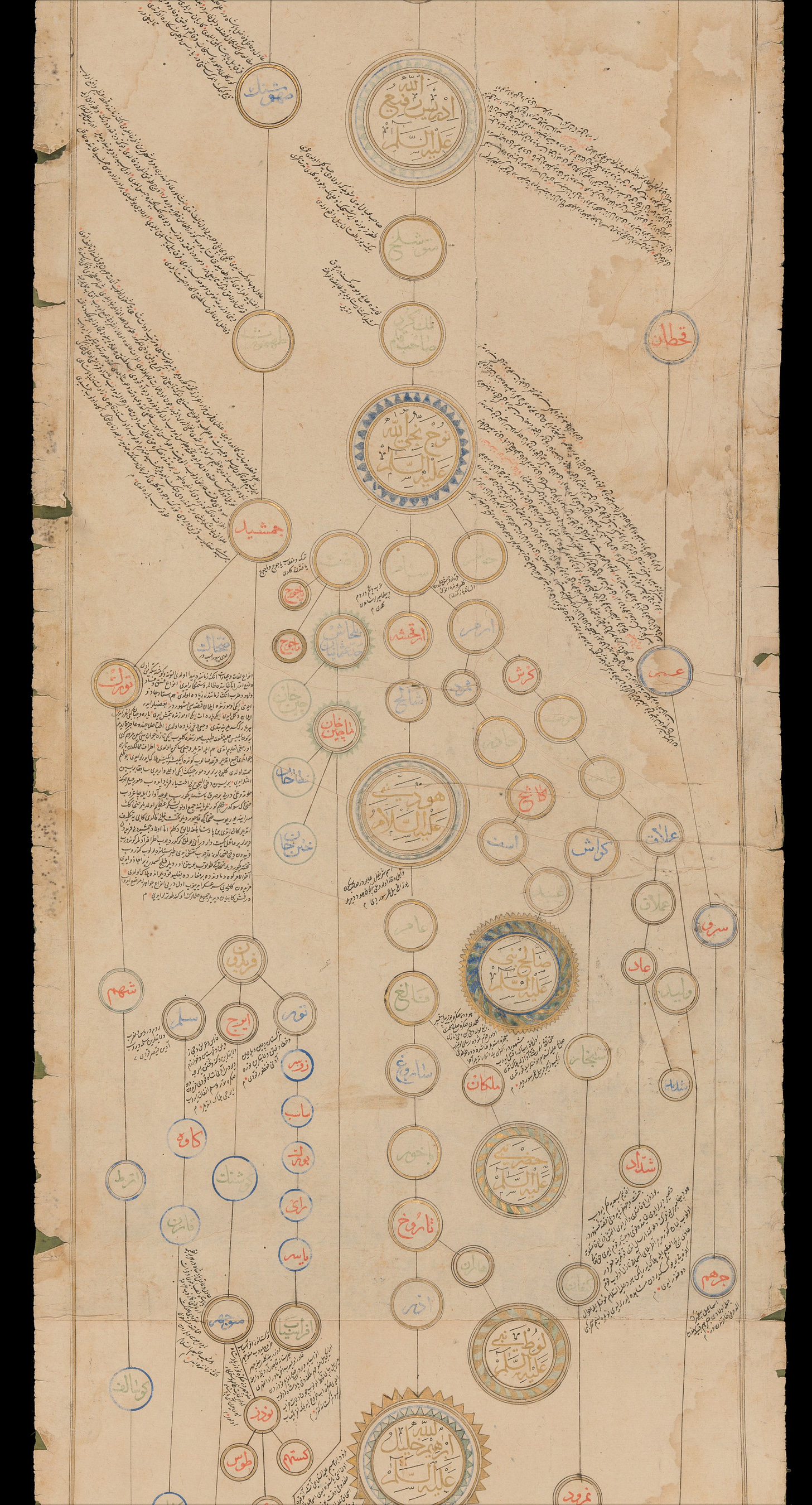

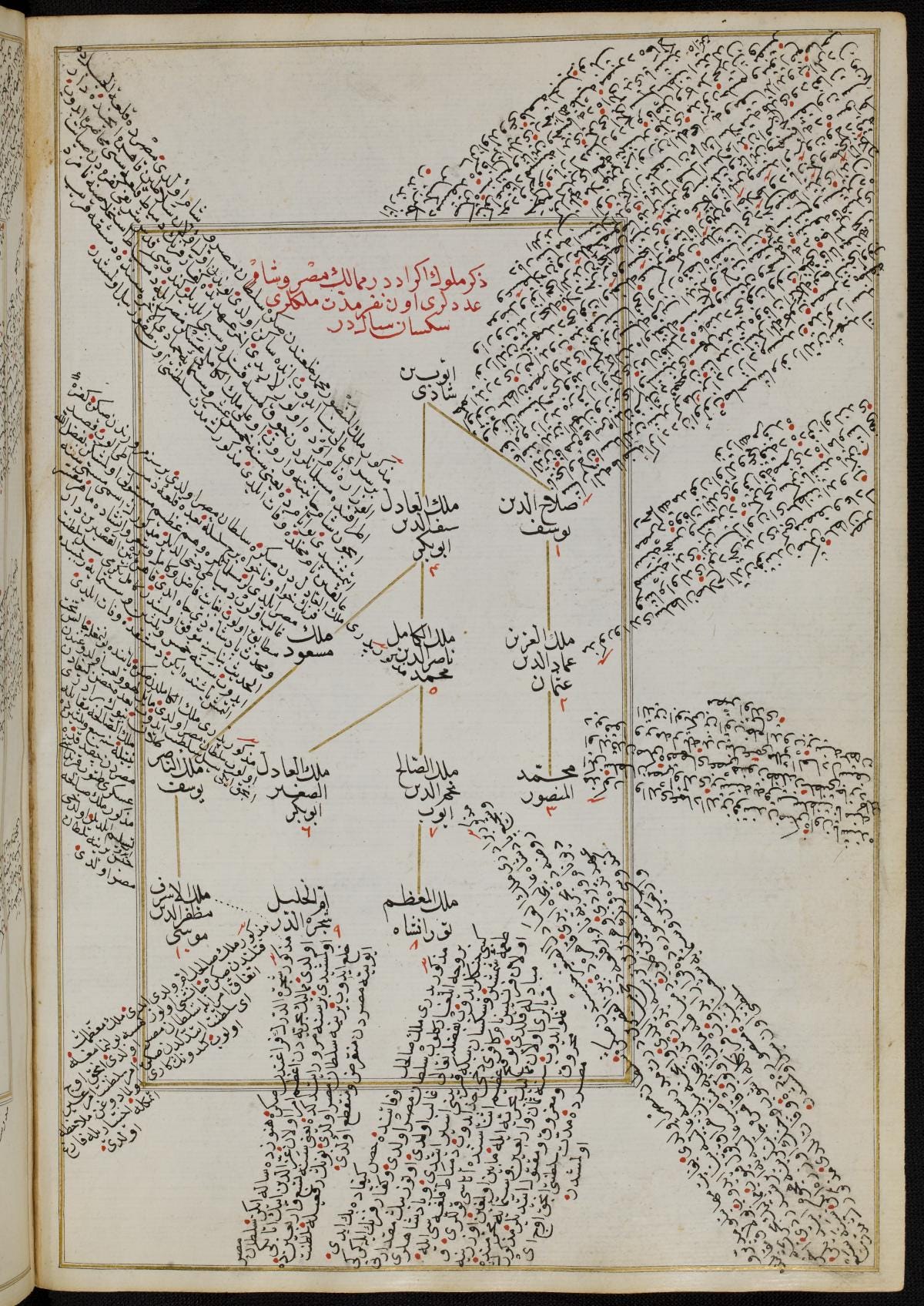

And so we come to the central theme of this essay: a visually spectacular genre, if that is what we should call it (and I do think it is generally apt), of early modern Islamicate manuscript production (though not at all limited to that world, as we will see), the ‘genealogical chart,’ but what I think is better understood as a form of visualized universal history, a condensed and visually-rich expression of human history, always commencing at the same point but then diverging in the routes down the genealogical line. Even without being able to read the Arabic script texts one can get a good sense of the visual dynamics of these works just by looking at them, and so before we think about what these works might have done as cultural technologies of visualizing and participating in the long flow of time, here are several examples, written in Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Turkish, all dating from the 17th century to the middle of the 19th:

‘Data visualizations’ strikes me as a perfectly suitable description of these works, even if we are not used to thinking of medieval and early modern manuscript cultures in such terms. Have a look at the screenshot of thumbnails of Petermann I 68, a universal history/genealogy of numerous Islamic dynasties as well as lineages of shaykhs, qadis, and many others:

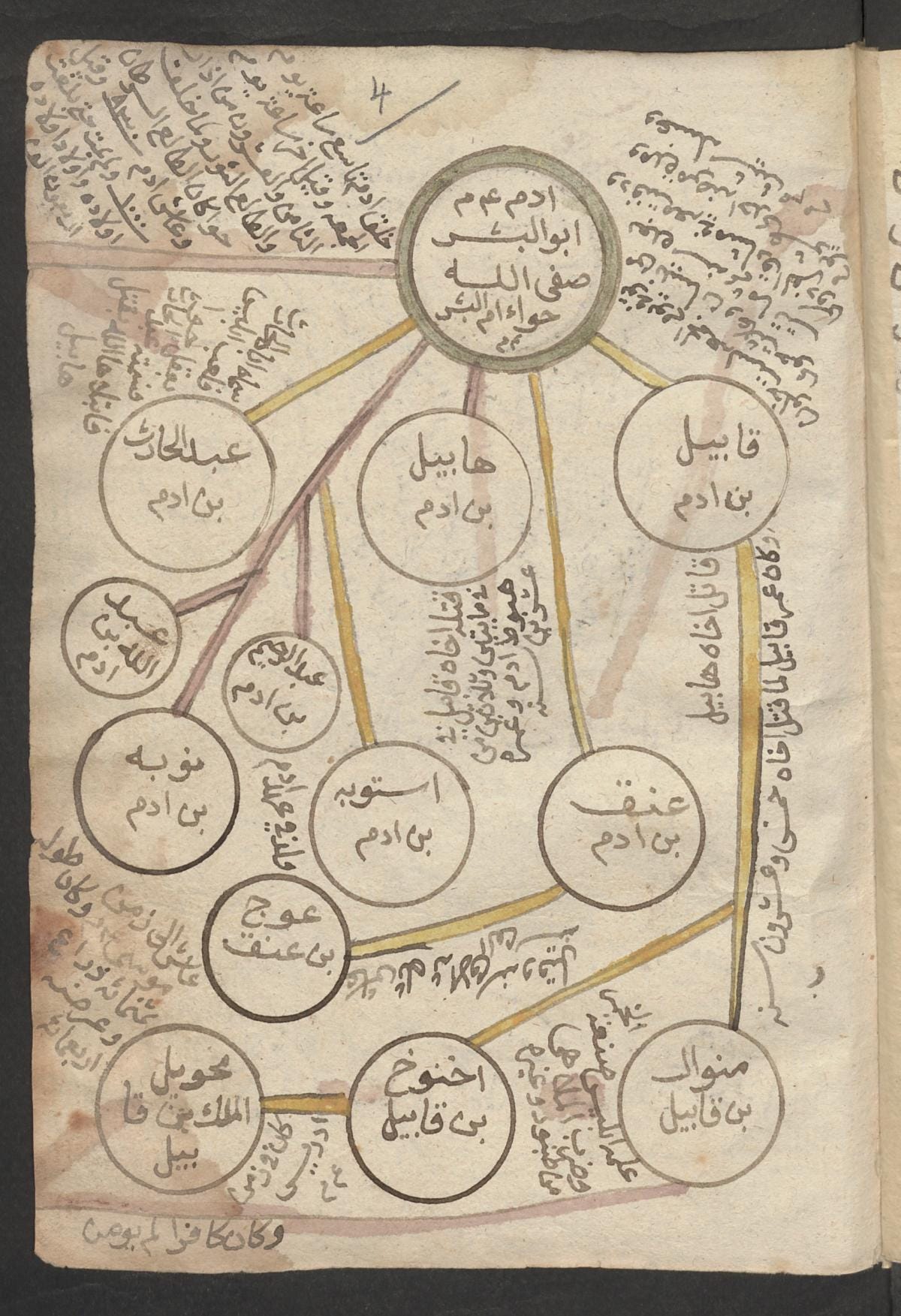

Or, with rather different concerns and influences in mind (in this case more the marginal textual practices of scholarly manuscripts), this early 17th c. Ottoman condensed history, which also hearkens back to an older form of rendering genealogies in more tree like fashion:

Here it as if (and maybe this is what in fact happened) an ordinary text of history has been subdivided and spatially rearranged in a whirl of texts, each block oriented to a name in the timeline, a fine example of a scribe maximizing manuscript affordances. The complexity and play of space and color and line is especially visible in thumbnail view (and note how vividly the Ottoman dynasty is marked out towards the end):

Of course we are cheating a bit: these are primarily codices, not scrolls, so any perusal of the ‘data’ would have required flipping through the pages, mentally connecting the previous visualizations (scrolls present their own possibilities, though they do not seem to have been as frequently used, probably because they become rather unwieldy at a certain point of length). Digital affordances give us an additional perspective, highlighting the variability in precise layout and decoration, as well as the visual signals that these different styles of rendering text and framing devices might convey.

Regardlesss of precise style, the content of these manuscripts is broadly similar: beginning with Adam, they trace human history forward under the figures of various persons, some readily recognizable as hailing from ‘sacred’ history, indeed from salvation history, leading up to Muhammad and his descendants. But other figures are present too, representatives of other currents of human history, the details depending on the author, location, period, and so on. Dynasties and their rulers and the descendants of rulers figure prominently, though we also see genealogical charts featuring saintly lineages as well. In terms of sources, while the interplay of authorities and the ways in which scribes sampled, modified, and condensed existing historical sources requires further study, in general these works drew upon existing historical compendia, in particular the genre of the universal history, from Adam to the present. In short, these works present the long span of human history as early modern audiences understood it under the figure of prominent (and, to be sure, some rather less prominent) persons, the linkages of genealogy also marking the passage of time all the way down to the scribe’s present. In some cases illumination identifies the most important figures, in other cases there is a general flattening of distinction, a cascade of name-bearing circle after name-bearing circle. Dates feature in the descriptions and the de facto ‘metadata’ of some of the elements, allowing the reader to trace the progress of time from page to page.

Part of what is going on here is clearly a response to a perceived problem that began to appear in the late medieval period, and which has continued apace to the present: the sense of information overload, of having more data in more forms than one can reasonably handle. Islamicate authors discuss this issue, and even more frequently we can see schematic attempts to deal with information overload. In this case, histories and genealogically arranged biographical dictionaries, among other works, had proliferated with both the passage of time and the expansion and intensification of Islamicate scholarly traditions. These condensed, visualized universal histories provided a much easier entry into the accumulated knowledge of the past, describing chronology and relationships through a visually rich spatial ordering of names and text blocks.

This genre and the concerns that helped to generate it were not unique to the Islamicate context. Now, I am not a Western medievalist by professional training, with many years now lying between now and my last serious dives into the history of the medieval Latinate world, so I can only give a brief impression of the late medieval manuscript productions (it’s hard to know what to call these things—they’re not really ‘texts’ in the usual sense, and not all of them are even codices!) that closely resemble our Islamicate universal history/genealogical visualizations. Whether we should understand it as the ‘origin point’ or not for the overall tradition, surely one of the most important ‘data visualization’ universal history of the late medieval period was Peter of Poiter’s Compendium historiae in genealogia Christi, of which there are many, many copies, in both codex and scroll format. We need only look at the following early 13th century example to see obvious parallels in the schematic and textual format of this work with our somewhat later Islamicate exemplars:

We also see works of a somewhat more ‘secular’ genealogical and political nature that work along similar principles of data visualization and place their ultimate subjects in the frame of universal history, such as this scroll from late 15th century England:

Can we draw a continuous line from the Compendium historiae’s format, and that of similar works of the late medieval period, to that of our early modern Islamicate history visualizations? I can’t say for sure, but it is striking that the particular style seen in the examples above—the use of roundels connected by lines, encompassed by text blocks, all of it frequently illuminated—does seem to only appear in Islamicate contexts around the 16th century; previous genealogical trees were just that, branching trees, fairly simple and intuitive diagrams that have probably been convergently evolved the world over. The late medieval universal histories and universalizing genealogical works are more complex, and so seem less likely to be examples of convergent cultural evolution like the Maya and Ottoman calendric works, and more of some genealogy of transmission and adaptation. It is possible that Armenian scholarly communities provide a point of contact—certainly there were Armenian manuscripts of universal history in condensed visualized form, which seem to draw upon both Latinate and contemporary Islamicate exemplars. The seventeenth century ‘abridged Bible’ of Serapion of Edessa, for instance, incorporates elements reminiscent of (and in some cases clearly drawn from) Latinate, Islamic, and Armenian traditions:

That said, convergence certainly remains a possibility, due to shared concerns across western Eurasia with the nature of history, the integration of salvation history with the more mundane, and the need to condense large accumulated bodies of knowledge into more manageable formats.

As such, regardless of routes of transmission or the dynamics of cultural convergence, it is certainly the case that these sorts of manuscripts would have been immediately recognizable across cultural, religious, and linguistic boundaries. They realized a highly commensurable form of data visualization, one that requires little explanation even today. In these works historical time has a starting point, with the question of origins and genealogy—literally and more metaphorically—taken as givens of interest. Such questions not only remain of interest to us today, we have in fact pursued them right here. These are durable cultural models and technologies of meaning-making indeed.

iii. on charting the past and the discovery of deep time

We tend to think of homogenization of time, visualization of data at scale, and so forth, as distinctly modern things, and in a way they are—and yet. The universal history data visualizations we have seen, whether of Latinate or Islamicate derivation, accomplish a sort of homogenization of time, a reduction of large periods of history to manageable scales of data visualization. They let the viewer ‘walk’ through time, and quite literally see the connections between his time and the past.

If Darwin’s ‘revolution’ and the slightly prior ‘discovery of deep time’ did in fact change many things in our shared epistemic universe (though not necessarily in the way that we usually imagine, but that’s another story), it did so using epistemic technologies and methods with a very long genealogy, which have themselves continue to exert a certain force within our thinking. Indeed, one of the striking features of the above visual universal histories is the degree to which the impression of time and space they give is really quite vast and complex: Peterman I 68, in particular, is a tour de force in visualizing universal history, with a truly impressive sheer visual mass that is even more striking when one considers it was all hand drawn and written! These charts simultaneously convey the depth of history and its complexity while also making that depth and complexity legible and navigable.

When this sort of technology is used to convey the contours of deep time it is arguably less successful, in part because we lack lived frames of reference through which to view timelines of evolutionary history or the formation of the cosmos. The lines and circles in the early modern genealogical chart move in a generational rythm, one which we can ‘feel’ with some degree of reflection as we ourselves move forward in the same units of time. The passing of thirty years is something that I can at least dimly sense, having passed through three decades myself (now approaching four decades…). But there really is no frame of reference within my lived experience for comprehending a line that captures three million years, much less three billion. Exercises such as imagining the universe’s history as taking place over a day or a week help to grasp the relative chronological distance or duration of various moments and processes, but I don’t think they bring us any closer to an emotional or phenomenological sense of that passage of time. It is only really in certain geological settings, in which, with a bit of interpretive knowledge framing what one is experiencing, the depth and weight of long periods of time can be seen and indeed felt, that it really sinks in.

As I’ve written about before, I’ve found few places in which this sense of deep time is so palpable as the Calvert Cliffs of the Chesapeake. In the grand scheme of things the chronology captured in these deposits is not especially vast, amounting to a few million years total (and generally less depending on one’s particular vantage point). What ‘works’ as almost a sort of massive-scale data visualization with these deposits is the ease with which they can be seen and interpreted, the constant shearing-off of cliff face leaving the fossils and sediments in sharp relief, the colors vivid, the marine fauna (and the odd flora floated down on ancient rivers) sticking out from the cliffs akin to many illustrations of the geological column. But unlike an illustration, which makes the passage of time feel manageable, confronted with even a tiny slice of it in real life it just feels enormous, the sheer weight and depth of the time represented in the rise and fall of the ancient ocean and its ecological communities vivid and present.

So. To return to our early modern Islamicate (and beyond!) technologies of time and relation, it is perhaps their conveyance of relationship and historical complexity that is most successful in these manuscripts, and which we might do well to emulate in our own works of data visualization. So often, whether in lamenting or praising it, we see industrial modernity as a sharp discontinuinity, our relationship with past worlds passing through a blurred boundary on the path backwards, a fundamental incomensurability arising as a result. In the face of geological time, of the deep past, we tend to feel something very similar: we stand outside looking upon the archive of the earth, unclear as to how if at all we relate to it except in the most abstract sense.

What is often missing is the factor that gives our early modern data visualizations their overall coherence, I think, whether they were of Islamic or Christian origin: the conviction that time has an internal unity due to its being structure by God’s salvific work in history, of divine providence structuring or otherwise working within the whole arc of time. I suspect—though more research needs to be done on this point—that along with the political and historiographic work that these manuscript charts did they also played a theological and devotional role, letting the viewer travel along that arc of salvation history and perhaps even to imaginatively ‘encounter’ various figures along the way.

And to be sure they had a political purpose, too, though I am always cautious around these questions, in large part because the audience of these productions is not entirely clear. Which is to say, I am not sure that an Ottoman genealogical scroll (which in fact encompassed a vast sweep of the world’s history as viewed through the lense of salvation) can be described as an instrument of ‘propaganda,’ given that it probably did not leave the palace. Rather, it probably served to reinforce for the sultan and his household their own sense of cosmic significance, whether that was reflected in the sultan’s saintly status or simply in his place in the chronological unfolding of God’s salvific will and direction. For other examples of this genre the political implications are far less clear, nor do I know what their actual quotidian function was. Certainly some of them show extensive signs of use: perhaps readers/viewers returned to them in order to map out time, to think through the unfolding of the past as it flows through one person after another, right up to the present, embodied in the spectacular orb of the living ruler. The lines running back in time, back ultimately Adam, via Muhammad, signaled perhaps a cosmic stability, a reassurance that history made sense, even when, as was surely often the case in the early modern world, it was not clear from everyday observation.

We in the present are not that different, really. There is some comfort in relativizing our place in time, in subsuming our sense of crisis or duty or whatever it is in the vast flow of time. Our charts and maps and visualizations and mental constructions of the past are also products of meaning-making and meaning-seeking, suggesting a deep, fundamental need in the human psyche, our cultural technologies ultimately tending to converge even when they are not directly genealogically connected. Where that need comes from, and all of what it might mean—a full exploration of those questions will have to wait for another time.